In this article I’ll explore St. Luke’s, the Episcopalian (Church of England) church in Little Bay, and the influences upon it from other institutional powers represented in the town. The Episcopalian reverends were influenced by the Baron’s leadership despite his absence, the rising power of the town’s Temperance movement, and the popular interest taken in native artifacts found in the area. Taken together I believe these interactions demonstrate the unique culture of the town which I’ll explore through Little Bay’s first three Episcopalian reverends; Clift, Turner, and Pittman.

In this article I’ll explore St. Luke’s, the Episcopalian (Church of England) church in Little Bay, and the influences upon it from other institutional powers represented in the town. The Episcopalian reverends were influenced by the Baron’s leadership despite his absence, the rising power of the town’s Temperance movement, and the popular interest taken in native artifacts found in the area. Taken together I believe these interactions demonstrate the unique culture of the town which I’ll explore through Little Bay’s first three Episcopalian reverends; Clift, Turner, and Pittman.

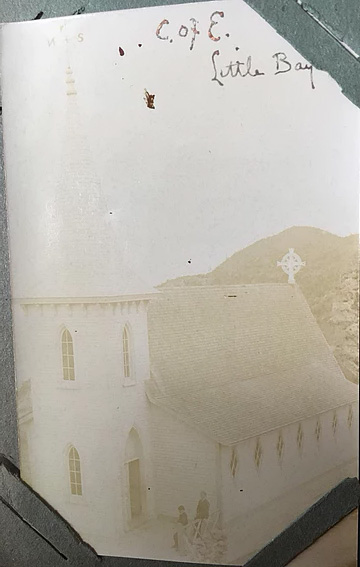

The first Episcopalian reverend to arrive in Little Bay was Rev. Theodore Clift who due to his 1883 arrival just missed the exodus of the Baron and his German speaking Presbyterian congregation. Clift was responsible for the construction of his church and establishing his religion’s presence in Little Bay. His church, St. Luke’s, would go on to serve as something of a symbolic legacy for the Baron’s influence on the early town. St. Luke’s began construction late in 1884 after a failed attempt to buy the unoccupied church from the Presbyterians. The building was completed in the spring of 1885 and paid for with a bazaar called the Fancy Fair. The event was held at the Skittle Alley prior to it being shut down by the town’s Temperance Movement in 1887. Rev. Clift seemingly shifted from supporting the Skittle Alley in 1885 to being firmly entrenched in Temperance by 1887. The Fancy Fair like other bazaars was organized by a committee of women from their respected denomination. I suspect this was influenced by the power of Temperance as well.

Planning started in the summer of 1885 for the Fancy Fair to support the church’s construction. Donations of money or fancy articles were requested by the ladies who composed the event’s committee (TS June 1885). That bazaar which was held at the Skittle Alley in October was praised as “the event of the season” with its tables “profusely laden with goods. It would be difficult to say whose table presented the most attractive appearance [but] the refreshment table under management of the popular school-mistress, Miss Ross [. . .] was largely patronized by the young gentlemen of the place” (ET Oct 1885). Mrs. Diem was the president of the event’s committee.

Planning started in the summer of 1885 for the Fancy Fair to support the church’s construction. Donations of money or fancy articles were requested by the ladies who composed the event’s committee (TS June 1885). That bazaar which was held at the Skittle Alley in October was praised as “the event of the season” with its tables “profusely laden with goods. It would be difficult to say whose table presented the most attractive appearance [but] the refreshment table under management of the popular school-mistress, Miss Ross [. . .] was largely patronized by the young gentlemen of the place” (ET Oct 1885). Mrs. Diem was the president of the event’s committee.

Rev. Theodore Clift left on good terms in 1888. He was replaced by Rev. Harward Turner that year. Turner presided over the funeral of Mrs. Diem. Hers was a noteworthy loss and a “long procession walked to the Church of England and were there met by the Rev. Mr. Turner who, besides the usual service, preached an appropriate discourse. The congregation then went to the graveyard and left there the remains of the deceased. Mrs. Diem [was] greatly missed as a Church worker and at her home by her large family” (TS Jan 1888).

Turner got into trouble quickly and was accused of drinking. He publicly denied it but it’s interesting to ponder how this would have played out with the town’s Temperance Movement. Rev. Turner would leave town that year for an extended vacation from which I don’t believe he returned. It’s my opinion that he was ran out of town by the power of Little Bay’s Temperance effort. He didn’t even last a year. He was still in charge, however, when St. Luke’s was adorned with a spire donated from the Bette’s Cove Presbyterian church. This hybridization was of note and largely symbolic of Little Bay’s open-minded approach to mixed denominations.

The town’s opened minded culture can be traced back to the Baron’s original influence. Little Bay wasn’t the Baron’s first Newfoundland town, that honour goes to Bette’s Cove. The first church in Bette’s Cove was named “Christ Church” and as in Little Bay the first church was Presbyterian but built to serve mixed denominations. This seems to be the case in all the communities the Baron created. When Christ Church was eventually moved to Little Bay its body became the town’s second Public Hall. That same building was eventually moved to Springdale where it became a Masonic Lodge. What’s really interesting is what became of Christ Church’s spire. The spire ended up adorning St. Luke’s. Jessie Ohman commented on the unusual nature of the hybrid building writing “Fancy a Presbyterian spire on an Episcopalian church and that in Newfoundland!” (Ohman 1892).

This sentiment was expanded upon in the writing of the Methodist Rev. James Lumsden after he’d spent a year in the town. He wrote of the unusually unified approach the town had to denominational religion stating that “a pleasing feature of life in Little Bay was the good feeling that existed among the churches, the Roman Catholic priest, Episcopal clergyman, and Methodist minister setting an example of friendliness which pervaded the community. There was something in the air of the place that [. . .] would have frowned down bigotry and made it impossible for it to thrive” and he goes on to give examples of experiencing this. He reflects on how he preached there as a Methodist minister in a Presbyterian church to a mixed denomination. His surprise at their cooperative attitude demonstrates how unusual it was. He further notes the way the religious leadership of Little Bay worked together to coordinate the population of the town to raise funds in support of St. John’s after the capitol city suffered its famous fire. Lumsden suggests that the example set by Little Bay could be followed elsewhere to the benefit of all (Lumsden, P.187-188). I’ve found numerous examples of this behaviour in my research including the use of the Episcopalian school-house by a committee of Methodist ladies for a bazaar to raise funds for their own church.

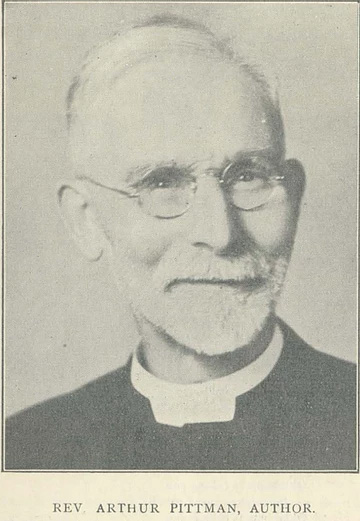

Following the departure of Rev. Turner in 1888 the Church of England would send Rev. Arthur Pittman. He was the town’s longest running Episcopalian clergy and would remain in Little Bay until 1913. The Episcopalian church in Newfoundland was organized from a number of missions with Little Bay as part of the Green Bay mission overseen by the Rural Dean of Notre Dame Bay. Rev. Arthur Pittman would occupy all of these positions over the course of his career. Pittman was working as a schoolmaster in Tilt Cove when Little Bay started in 1878 but he enrolled in Queen’s College in 1883 and thus began his career in clergy. After Pittman arrived in Little Bay in 1888 he took an interest in the area’s original inhabitants. The town had an interest in public literacy and popular science as I’ve explored in other articles. I suspect this mindset to have influenced Pittman’s amateur archeology.

Following the departure of Rev. Turner in 1888 the Church of England would send Rev. Arthur Pittman. He was the town’s longest running Episcopalian clergy and would remain in Little Bay until 1913. The Episcopalian church in Newfoundland was organized from a number of missions with Little Bay as part of the Green Bay mission overseen by the Rural Dean of Notre Dame Bay. Rev. Arthur Pittman would occupy all of these positions over the course of his career. Pittman was working as a schoolmaster in Tilt Cove when Little Bay started in 1878 but he enrolled in Queen’s College in 1883 and thus began his career in clergy. After Pittman arrived in Little Bay in 1888 he took an interest in the area’s original inhabitants. The town had an interest in public literacy and popular science as I’ve explored in other articles. I suspect this mindset to have influenced Pittman’s amateur archeology.

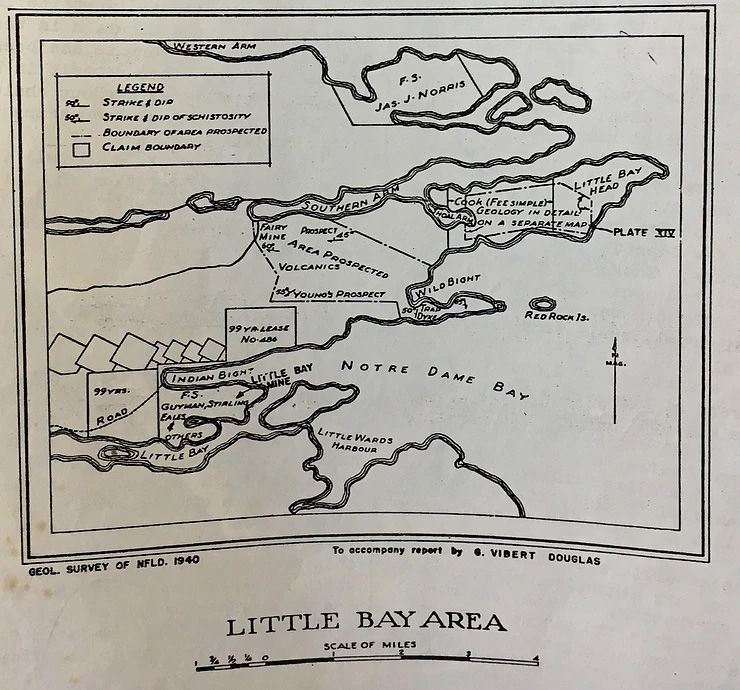

I’ve uncovered scattered references to the pre-European history of Little Bay. Prior to the start of the town in 1878 Little Bay was referred to as Indian Bight and James Howley, while surveying the area immediately prior to the settling of the town noted impressions left by previous native habitation. The 1880 census for Little Bay lists an area called Indian Town which does not appear on future censuses. There was a discovery in a cave at nearby Pilley’s Island in 1886. Two human skulls were found there with an assortment of objects including several children’s toys. This find along with other local discoveries contributed to an interest in native artifacts as recorded in Howley’s journals. Rev. Pittman began shipping native artifacts to the Royal Museum in England by 1893. There they remain with their accompanying letters which I have been fortunate to access. In those letters he details archeological discoveries and guesses as to the function of the objects submitted. Beyond this hobby he would also go on to become a published and popular writer in Newfoundland and by 1905 was appointed Rural Dean of Notre Dame Bay. He appears to have remained in Little Bay after the loss of St. Luke’s to the fire that destroyed the town the previous year.

It’s important to understand the symbolic weight of a building like St. Luke’s. It was the physical manifestation of Episcopalianism in Little Bay and the clergy who administered from it enacted the values of that institution. St. Luke’s was a building, yes, but it was not only a building. From it Episcopalianism was lived through its clergy. They interacted with other denominations such as Presbyterianism, cultural movements such as Temperance, and scientific disciplines such as archeology. These men, without ever having met the Baron, promoted the multi-denominational values he’d built into the town’s culture from the get-go. Heck, St. Luke’s served as a physical testimony to the hybridized nature of Little Bay’s culture. Further, Clift and Turner’s positions on Temperance were relevant to their power there while Pittman is yet another example of the intellectualism prevalent in the early town. I also find Arthur Pittman’s interest in his town’s pre-history a bit poetic. It’s akin to our own interest in the Little Bay he experienced. Like Pittman we are looking backward and dimly seeing the past through impressions left by the people who were there. I’m trying to make that past a little less dim. I hope this helped. Thanks for reading!

Sources:

Twillingate Sun

Evening Telegram

Harbour Grace Standard

St. John’s Colonist

St. John’s Evening Herald

The Water Lily (Ohman)

Across Newfoundland with the Governor (Harvey)

The Skipper Parsons (Lumsden)

Geological Survey of Newfoundland (Howley)

The letters of Rev. Pittman (Royal Museum)