The Baron drew me in. I’d started researching my mother’s hometown of Little Bay while working on her genealogy. Growing up I’d often heard it said there that the town had once been one of the biggest on the island but the true scale of the history was jaw-dropping. I became enthralled by it but it was the Baron Franz von Ellershausen who really floored me. The town’s founder was a German Baron. They spoke German in this 19th century Newfoundland mining town! I was hooked.

The Baron drew me in. I’d started researching my mother’s hometown of Little Bay while working on her genealogy. Growing up I’d often heard it said there that the town had once been one of the biggest on the island but the true scale of the history was jaw-dropping. I became enthralled by it but it was the Baron Franz von Ellershausen who really floored me. The town’s founder was a German Baron. They spoke German in this 19th century Newfoundland mining town! I was hooked.

The story starts with a shipwreck in Nova Scotia. Suddenly stranded on the cold coast were thirty German families. A wealthy German industrialist came to their aid. The year was 1863. The Baron Franz von Ellershausen was a prominent figure. An educated man, knowledgeable in engineering and metallurgy, a man of depth and emotionality, prone to outbursts and excessive generosity he built for them a town. A testament to his hubris he named it after himself; Ellershouse. He built his home there, a grand mansion also named for himself – Ellershausen Manor. It still stands today as a heritage site.

A product of his time and resource, Ellershausen saw the world as his to shape. This was the age of grand engineering but also of social planning. The recognition of his greatness and altruism must have inspired him, for Ellershouse was only the first town the German Baron would found. In creating Ellershouse the Baron had saved thirty families, the act earned him their love and their loyalty. They would follow him anywhere and for many, that was going to take them to the island of Newfoundland.

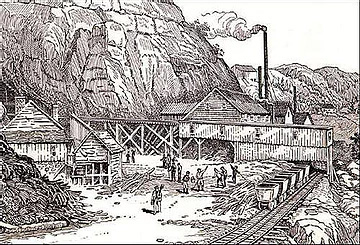

In 1874 Baron Ellershausen experienced his own shipwreck and found himself in Newfoundland by mistake. This accident proved fateful. Learning of the fledgling mining operations started on the island he immediately got involved in a mine in a town called Bette’s Cove. He called for his men and they went to work transforming the landscape. He had a telegraph line ran there. He was involved with the telegraph as early as 1876. Here’s where it gets weird. The line was ran to Little Bay early in 1878, seemingly before there was any reason to put a town there. Ellershausen was publicly in telegraph politics even offering to put some of his own money up to secure the line. The oddity of the telegraph timeline sets the stage for a series of conspiracies.

In 1874 Baron Ellershausen experienced his own shipwreck and found himself in Newfoundland by mistake. This accident proved fateful. Learning of the fledgling mining operations started on the island he immediately got involved in a mine in a town called Bette’s Cove. He called for his men and they went to work transforming the landscape. He had a telegraph line ran there. He was involved with the telegraph as early as 1876. Here’s where it gets weird. The line was ran to Little Bay early in 1878, seemingly before there was any reason to put a town there. Ellershausen was publicly in telegraph politics even offering to put some of his own money up to secure the line. The oddity of the telegraph timeline sets the stage for a series of conspiracies.

Prior to 1878 there is no Little Bay. The area was a wilderness used as a hunting ground for the Colbourne family out of Wild Bight. A Robert Colbourne discovered the deposit while hunting caribou. His claim was purchased for some flour and tea. His name was only the first to change on the claim, however, and what happened next marks the second part of our conspiracy. The ownership of the property was filed by Ellershausen’s business partner Adolph Guzman and another man whose name was replaced illegally. Ellershausen was scheming with Newfoundland’s Premier William Whiteway. Whiteway who acted as Ellershausen’s power of attorney. Today the town’s land is still owned by Guzman as a result of this legal fancy work.

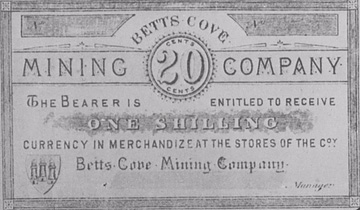

The Baron had Little Bay physically built almost overnight and influenced every facet of its culture. He brought his German workers with him from his shipwrecked Nova Scotian town and he appointed Little Bay’s leadership including the town’s surgeon and its first reverend. He moved the town of Bette’s Cove, men, machines, and buildings to the new site and within only a few short months his men had turned the wilderness into a fully functional community of over 500 people. The town quickly took world stage as the growing mineral industry was expected to overtake fishing and make Newfoundland a most lucrative colony. The town was ran by the mine management. The workers rented their homes and bought their goods from the company store with company credit. The prosperous community swelled to over 2000 people in short order making it one of the largest on the island.

The Baron had Little Bay physically built almost overnight and influenced every facet of its culture. He brought his German workers with him from his shipwrecked Nova Scotian town and he appointed Little Bay’s leadership including the town’s surgeon and its first reverend. He moved the town of Bette’s Cove, men, machines, and buildings to the new site and within only a few short months his men had turned the wilderness into a fully functional community of over 500 people. The town quickly took world stage as the growing mineral industry was expected to overtake fishing and make Newfoundland a most lucrative colony. The town was ran by the mine management. The workers rented their homes and bought their goods from the company store with company credit. The prosperous community swelled to over 2000 people in short order making it one of the largest on the island.

The Baron ran into some bad investments after this. After a failed attempt to drain a lake in Nova Scotia and a financially disastrous silver mine in Newfoundland his motivation for Little Bay dwindled. His friend and business partner Adolph Guzman had betrayed him and left the island while another partner had suddenly died. Their replacements did not live up to their predecessors with one involving the business in a bitter legal dispute. Worst of all his German workers had largely returned to their families in Nova Scotia and copper prices were down. He sold the mine.

The Little Bay mine was transferred to The Newfoundland Consolidated Copper Mining Company in 1881, however, at the same time the Newfoundland government decided to connect the town to St. John’s via railway. This is the third part of our conspiracy and one that took 100 years to unravel. American investors were purchasing the mining operations but also formed the Newfoundland Railway Company. Once it got out that they were behind both operations there was a public uproar over the blatantly vested interest represented. Rumours spread that the government was also secretly involved. They were right. Whiteway had threatened to resign if the Bill for the construction of the railway had failed.

The Baron, however, had a backup plan involving English capitalists that he was simultaneously hosting. Their presence was unlikely coincidental. He took a boat to England to secure more money. Just two weeks later, however, and also returning from England, came the Premier Whiteway while sharing the vessel with not only the very English investors now involved but the American businessman involved from the start, suggesting that they may all have been in cahoots from the beginning. The railway never made it to Little Bay but the project did move an awful lot of government money into other hands.

The Baron, however, had a backup plan involving English capitalists that he was simultaneously hosting. Their presence was unlikely coincidental. He took a boat to England to secure more money. Just two weeks later, however, and also returning from England, came the Premier Whiteway while sharing the vessel with not only the very English investors now involved but the American businessman involved from the start, suggesting that they may all have been in cahoots from the beginning. The railway never made it to Little Bay but the project did move an awful lot of government money into other hands.

I’d like to believe that the Baron wasn’t singularly motivated by greed. He had a vision of Little Bay surviving the loss of its mining industry. He wanted the town he’d founded to outlive its first resource. The telegraph line, the advanced wharfage, and the town’s almost-railway were a part of that. He’d been inspired by the success of his first town, Ellershouse Nova Scotia and his early intentions appear noble however profitable and more than a little ego-driven. He was a man of industry and vision who saw the ends as justifying the means. The Baron was willing to cross ethical lines to achieve his goals and maybe that tarnishes his achievements. He achieved much and failed often but it’s the scale of his attempts that I find most admirable. In the end, after a series of defeats, he abandoned his efforts in Newfoundland for Spain before eventually returning to Germany where he died in 1914, leaving Little Bay and Newfoundland to their fates.

Today, the Baron Franz von Ellershausen is the founding father of two Canadian towns; Ellershouse in Nova Scotia and Little Bay in Newfoundland. His engineering and leadership skills shaped the landscape of Little Bay. Most of where the town stands was underwater when he first arrived. A pond was in the way so he moved it. The influence he had on Newfoundland’s 19th century economy was immense and it’s difficult to imagine how much the history of the island would be different without him. What most fascinated me, though, was the social planning he employed. He designed not only Little Bay’s layout but also its culture. This wasn’t the Newfoundland history I’d been taught growing up and all of this from a small town I thought I already knew. This hidden little outport where I’d spent my childhood summers was once a gem on the world’s stage, a multicultural and posh community with an international port where the locals had a reputation for dressing stylishly and eating strange foreign foods like pineapples! I’m still blown away by it. The sources for this project come from everywhere as media covering the town was international. The impact of the place was immense and the 19th century history of the place stands in such stark contrast to the little outport that followed. Little Bay is a strange and fascinating part of Newfoundland history that was almost completely lost after a fire in 1904. The Baron plays a big hand in inspiring me to dig it up. I feel a kinship with the man who started the place. It’s a funny thing, getting to know dead people. The two of us, separated by time but connected through his discovery and my rediscovery of the same place – a journey from the Little Bay he made; to the one I grew up in.

Hopefully, by writing this, I connect you to this hidden history too.

As always, thanks for reading!

Sources:

Carbonear Herald 1879, 1881

Evening Telegram 1880, 1881, 1883, 1889

Harbour Grace Standard 1876, 1879, 1880, 1881

St. John’s Free Press 1877

St. John’s Terra Nova 1880, 1881, 1883

Twillingate Sun 1882

The Witness 1878, 1879, 1880, 1881, 1882

Our Country 1883, 1884

Newfoundland Almanac 1907

Across Newfoundland with the Governor 1879 (Harvey)

Geological Survey of Newfoundland 1881 (Howley)

Canadian Paper Money Journal 20/4, 22/1

Colonial Commerce (1915-1916)

Decisions of the Supreme Court (1884-1896)

Journal of the House of Assembly 1878

German Canadian Yearbook XVIII

Once Upon a Mine (Martin)

From Vikings to U-boats (Bassler)

Deck’s Awash vol. 21 no. 04

Encyclopedia of Newfoundland vol 5

Newfoundland Quarterly vol 8, 86