Little Bay was lively during the last decade of the 19th century. It could claim a unique culture with some unusual features, most notably were its openminded approach to religion and an odd contrast that was held there between alcohol and literacy. Explaining these features of Little Bay’s culture will require a deep dive into the experiences of its Presbyterian ministers – Archibald Gunn, William Scott Whittier, and James R. Fitzpatrick.

The story of Little Bay’s Presbyterian church begins in Ellershouse, Nova Scotia. As I’ve previously explored, Ellershouse was the first town that Little Bay’s founder, the Baron Franz von Ellershausen, created. There he requested the architect David Stirling build him a church that would serve his multi-denominational community. That church called Saint Louise still stands today. The Baron carried that sense of community cooperation and diversity with him to Newfoundland where his second town, Betts Cove, saw him doing the same. Christ’s Church was built there. Christ Church was “built and finished throughout by the Company for the use of the Presbyterians and Church of England” (The Witness, Aug 3 1878). It was “a very pretty and commodious erection, well finished in every respect and having every appliance for comfort. This [was] a Free Church in the true sense of the term” (Harvey p.80). Free Church in this context refers to its multi-denominational function. The majority of the town’s population attended its varied services.

I don’t think the Baron was singularly motivated by religion, however, as building a church was not his first social objective. He set to it only after the construction of the community’s school. Before there was a church “meetings were held in the Schoolroom” (The Witness, Aug 3 1878). Ellershausen’s motivation appears to have been community building itself and he aimed higher than its industry or even its physical infrastructure. Under the Baron’s leadership Betts Cove was a dry community. Selling alcohol was prohibited under threat of serious penalty. Harvey credited that as the reason for the ordered behaviour of the people there. He described “the absence of rows and street disturbances, and the comfortable aspect of the population” and further claimed that he “did not see any one under the influence of liquor.” He called the town one of the best regulated he had visited noting that “crimes of theft and violence [were] almost unknown despite its population being “from all quarters” (Harvey p.76-77).

The Baron was praised for his judgement which was “shown conspicuously in the selection of his officers” (Harvey, p.78). The officers were “all young gentlemen of good education, and [gave] a tone to the society of the place. During winter season they [gave] concerts, public readings, lectures, and occasionally engage in amateur theatricals, thus affording to the little community, pure and elevating recreation” (Harvey p.85). It was into this scene of cooperation and community building that the Presbyterian Reverend Archibald Gunn arrived in November 1878 and there remained as “the guest of Mr. Ellershausen for two months” (The Witness, May 3 1879).

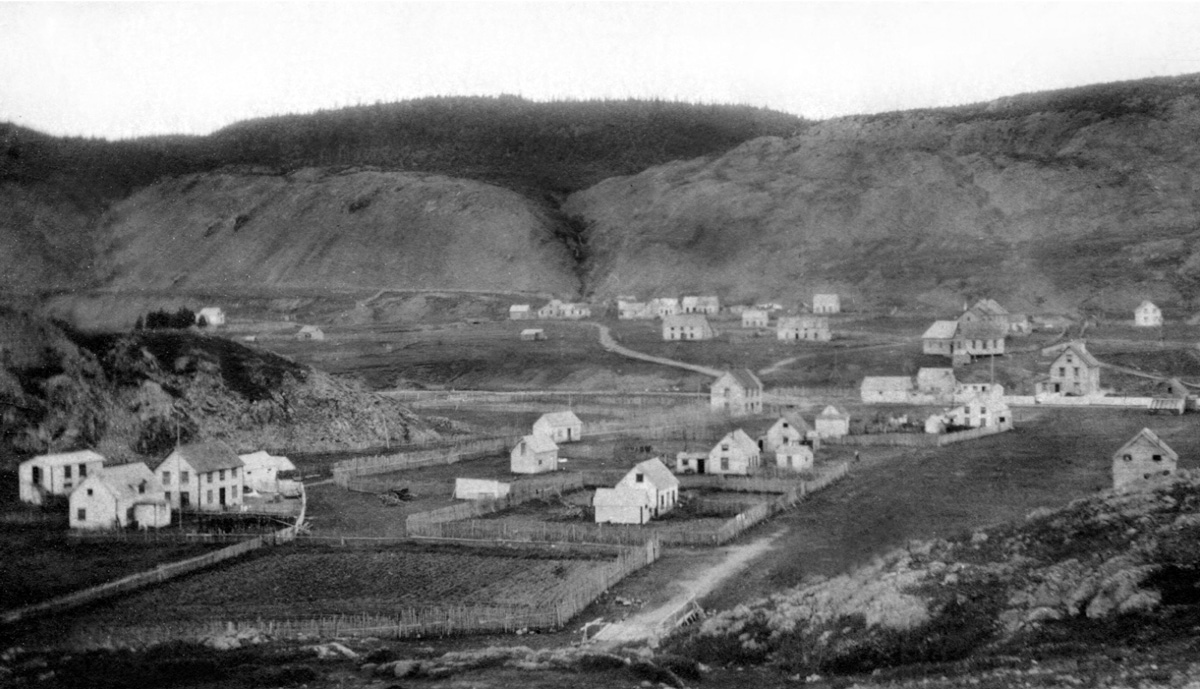

The Baron must have seen potential in him as he requested that Gunn move to his latest and largest community effort, the town of Little Bay which had just formed. I believe nearly all the original inhabitants of the town were thus selected. The Baron had a hand in everything. The find at Little Bay was all anyone could talk about in Betts Cove and it was anticipated to overshadow the rest of Newfoundland’s mining efforts. Reverend Archibald Gunn accepted “the request of Mr. Ellershausen [to move] to Little Bay [and live] with him and his manager Mr. Guzman. Little Bay [had] become the centre of the Company’s great mining district in Newfoundland. There [were] 1500 people [and] the mine [was] only a few months old. It [had] already done great things and greater things [were] expected of it” (The Witness, May 3 1879). Rev. Gunn arrived at Little Bay in January of 1879 (Moncrieff, p.119).

Gunn

The population of Little Bay was composed of many who had previously resided at Betts Cove. It was basically the same town relocated. Rev. Gunn reflected that “The masterly manner in which Mr. Ellershausen handled the whole affair was remarkable. The howling wilderness was in a few weeks converted into a straggling village supporting a busy population. The mine was an immense hive of industry. [. . .] There was a large population, but no clergymen to look after their spiritual wants. [. . .] the majority of Presbyterians had gone to Little Bay, and others were still going. Being invited [and] with consent of Presbytery [Rev. Gunn] took up [his] residence there” (The Witness, June 5 1880).

The population of Little Bay was composed of many who had previously resided at Betts Cove. It was basically the same town relocated. Rev. Gunn reflected that “The masterly manner in which Mr. Ellershausen handled the whole affair was remarkable. The howling wilderness was in a few weeks converted into a straggling village supporting a busy population. The mine was an immense hive of industry. [. . .] There was a large population, but no clergymen to look after their spiritual wants. [. . .] the majority of Presbyterians had gone to Little Bay, and others were still going. Being invited [and] with consent of Presbytery [Rev. Gunn] took up [his] residence there” (The Witness, June 5 1880).

The town was not yet a year old and Gunn was the first minister to arrive. He “reported that at the first communion service held in Little Bay in March 1879, both Episcopalians and Methodists attended and communicated” (Moncrieff, p.120). Rev. Gunn had his first service above the combined Telegraph Office and Surgery. It’s funny to picture Rev. Gunn preaching upstairs in the already crammed space while Postmaster Walsh and Dr. Stafford worked downstairs. “The building was small and not well adapted for [the] purpose. In course of a few months, a meeting was called to take into consideration the propriety of building a church” (The Witness, June 5 1880).

Rev. Gunn wrote that in the days that followed “Mr. Guzman subscribed the handsome sum of eighty dollars, and also gave us the beautiful site on which to build. Mr. Ellershausen subscribed the sum of two hundred dollars, and after treating us with a witty, pleasing and able speech, offered to advance us whatever further moneys should be required” (The Witness, May 3 1879).

The corner stone, composed of ore mined from Little Bay, was laid for the church on the 12th of March in 1879. “This stone was a block of copper and iron taken out of the mine and dressed for the purpose” (The Witness, June 5 1880). The Presbyterian church officially opened on the 7th of September. It was dedicated by Rev. Macneill who visited from St. John’s for the ceremony. The church had cost about $2000 and had a capacity between 200 and 300 people (Moncrieff, p.119). Rev. Macneill described the church as “a neat and pretty structure” that could be seen “lifting its modest spire amid the trees on the borders of the infant town.” On its first day “Rev. Mr. Gunn conducted the opening exercises.” Rev. Gunn was “labouring with much acceptance among the Presbyterians of the place” (HGS, Sept 20 1879). He was still the town’s only minister and in the spirit of the Baron’s communities all denominations attended his services (Moncrieff, p.120).

The corner stone, composed of ore mined from Little Bay, was laid for the church on the 12th of March in 1879. “This stone was a block of copper and iron taken out of the mine and dressed for the purpose” (The Witness, June 5 1880). The Presbyterian church officially opened on the 7th of September. It was dedicated by Rev. Macneill who visited from St. John’s for the ceremony. The church had cost about $2000 and had a capacity between 200 and 300 people (Moncrieff, p.119). Rev. Macneill described the church as “a neat and pretty structure” that could be seen “lifting its modest spire amid the trees on the borders of the infant town.” On its first day “Rev. Mr. Gunn conducted the opening exercises.” Rev. Gunn was “labouring with much acceptance among the Presbyterians of the place” (HGS, Sept 20 1879). He was still the town’s only minister and in the spirit of the Baron’s communities all denominations attended his services (Moncrieff, p.120).

Gunn wrote that “The spirit of bigotry is almost gone. All denominations attend our service. Some of our best friends are found among those not Presbyterian. May this good feeling continue” (The Witness, June 5 1880). The Baron aided the other denominations in the construction of their own churches and during the building of the Roman Catholic church “Ellershausen gave a relay of horses to haul the heavy timber to the plateau on the crest of the hill” (ET July 1903). However, after suffering a series of losses both economic and personal, Baron Ellershausen lost interest in his cause and started plans to sell the mine. This was devastating news. I suspect Gunn’s decision to leave was effected by the Baron’s waning interest in the community. Little Bay was saddened to see Gunn go. The mine management gifted him with a “Mineral Cabinet with selections from the various mineral deposits” as a memento of his time in Little Bay. They wrote “while we retain gems of thought from your mind, you will carry with you gems from our mines” (HGS June 19 1880).

In departing he praised the German leadership and stated “I would like to pay a well earned tribute of praise to Mr. Ellershausen for his generosity and magnanimity, and to Mr. Guzman for his extreme kindness and liberality.” He stated further “The ministers of Presbytery are already aware of the noble manner in which Mr. Ellershausen and Mr. Guzman have acted toward me as an individual, and towards our Presbyterian cause. I for one can never forget their kindness” (The Witness, June 5 1880).

Whittier

Rev. William Scott Whittier arrived from Halifax on a coastal steamer, the S.S. Falcon, on July 8th 1880 (TS). He reflected that his duties were both “ordinary and otherwise” (The Witness, June 17 1882). The Little Bay he inherited was not the same one Gunn had left and Rev. Whittier’s experiences differed from Gunn’s drastically. Frustrations are apparent in his writings and in a letter that November he wrote “We are down on the hard pan. The superstructure of organized society has yet to take form [and] intellectual night reigns to a sad extent” (The Witness, Nov 13 1880). He described Little Bay as expressing “as much as possible in broken German, bad English, and worse French” (The Witness, Feb 19 1881).

Whittier was an intellectual by nature. He was a recent graduate from the Presbyterian College in Nova Scotia where he had been the president of the student society and an editor for the school’s newspaper, ‘The Gazette’. Moncrieff notes the high quality of the letters he would write to the Presbyterian newsletter. In writing his Nova Scotian readership he asked them to imagine “lugging a stick of wood to school with you every morning throughout a Newfoundland winter under penalty of freezing if the sticks be not heavy! Is it any wonder that so few learn to read” (The Witness, Nov 13 1880). He proclaimed that reading was necessary for people to succeed in life and so focused his attention in Little Bay on the Sabbath School which was “attended by nearly all the Protestant children” (The Witness, June 11 1881).

Whittier was an intellectual by nature. He was a recent graduate from the Presbyterian College in Nova Scotia where he had been the president of the student society and an editor for the school’s newspaper, ‘The Gazette’. Moncrieff notes the high quality of the letters he would write to the Presbyterian newsletter. In writing his Nova Scotian readership he asked them to imagine “lugging a stick of wood to school with you every morning throughout a Newfoundland winter under penalty of freezing if the sticks be not heavy! Is it any wonder that so few learn to read” (The Witness, Nov 13 1880). He proclaimed that reading was necessary for people to succeed in life and so focused his attention in Little Bay on the Sabbath School which was “attended by nearly all the Protestant children” (The Witness, June 11 1881).

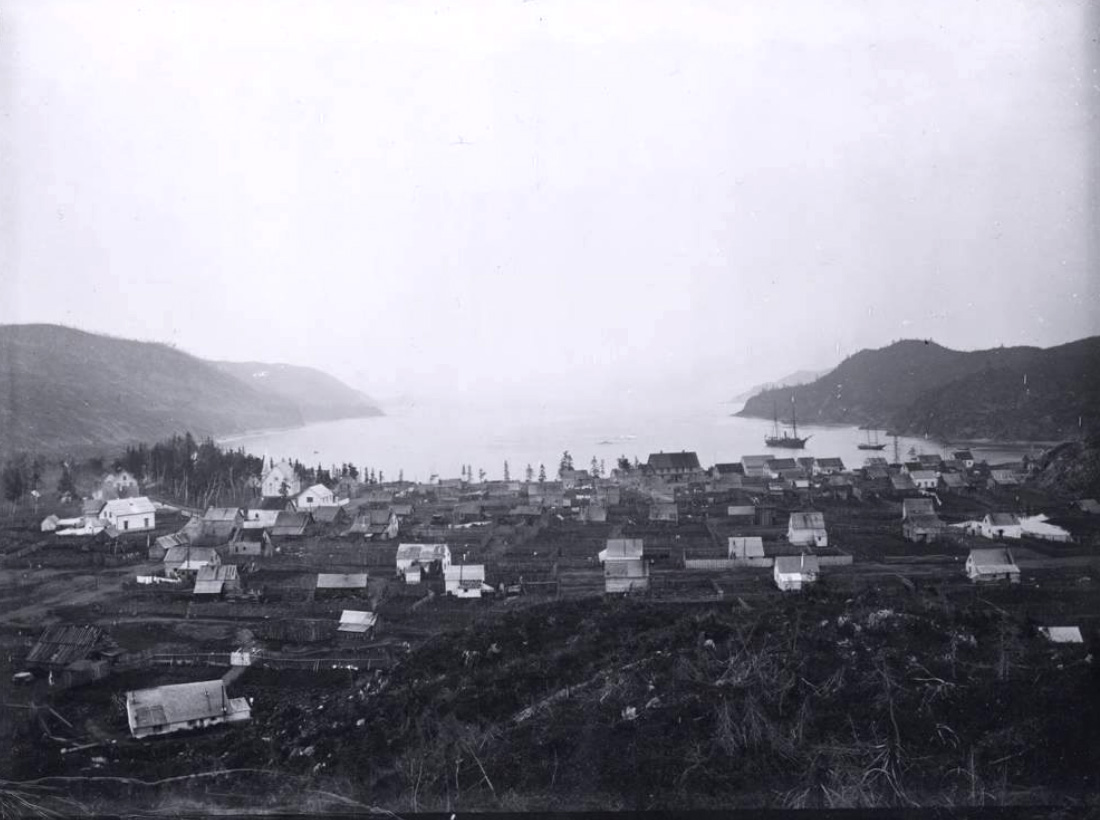

He described Little Bay as “a miniature German dukedom showing the characteristic ambition, energy and absolutism, having its circling lines of officials retiring by degrees” (The Witness, Feb 19 1881). The changing officials he mentions here regard the Baron’s sale of the property. A leadership change took place during Rev. Whittier’s stay in Little Bay. The Baron’s influence on its culture dwindled. There are also hints that the Baron’s goals were less loftily held after this and Rev. McNeil wrote that in political matters “it is neither pleasant nor prudent for ministers to mingle. Suffice it say, that as the result of Mr. Ellershausen’s enterprise [. . .] Newfoundland appears to have entered upon a New Era of her history. Whether it shall prove to be [. . .] only a temporary glint of sunshine to be followed by clouds again, I am not prophet enough to determine” (The Witness, Feb 18 1882). With the German departure Little Bay lost the upper class who had given “tone to society.” During Whittier’s occupancy people left for all parts and he wrote that “They are scattered far who met on the rough shores as strangers and worshipped in the little church together [. . .] So the results of our mission are to be found in the better lives of those who have come and gone — or then they are to be found nowhere.” He pointed out that “Most of those new employed in the mines are natives of Newfoundland” (The Witness, June 17 1882).

He described Little Bay as “a miniature German dukedom showing the characteristic ambition, energy and absolutism, having its circling lines of officials retiring by degrees” (The Witness, Feb 19 1881). The changing officials he mentions here regard the Baron’s sale of the property. A leadership change took place during Rev. Whittier’s stay in Little Bay. The Baron’s influence on its culture dwindled. There are also hints that the Baron’s goals were less loftily held after this and Rev. McNeil wrote that in political matters “it is neither pleasant nor prudent for ministers to mingle. Suffice it say, that as the result of Mr. Ellershausen’s enterprise [. . .] Newfoundland appears to have entered upon a New Era of her history. Whether it shall prove to be [. . .] only a temporary glint of sunshine to be followed by clouds again, I am not prophet enough to determine” (The Witness, Feb 18 1882). With the German departure Little Bay lost the upper class who had given “tone to society.” During Whittier’s occupancy people left for all parts and he wrote that “They are scattered far who met on the rough shores as strangers and worshipped in the little church together [. . .] So the results of our mission are to be found in the better lives of those who have come and gone — or then they are to be found nowhere.” He pointed out that “Most of those new employed in the mines are natives of Newfoundland” (The Witness, June 17 1882).

This marked the German exodus from the town. Most of the “Presbyterians who had come from Nova Scotia [. . .] had practically all returned” (Moncrieff, p.122). The miners had come “from the Maritime Provinces, as there were then no miners in Newfoundland.” The new population was not Presbyterian, a point which Rev. Whittier expressed with some contention stating “I met them on the ground of the great truths and of good living, not on the grounds of a special propagandist. When all the honest work in the world is done it will be time enough to take to sheep stealing” (The Witness, June 17 1882). Sheep stealing likely refers to the practice of converting members of another’s denomination to one’s own. It’s apparent that he felt he was being pressured to keep the Presbyterian numbers up despite the exodus of the denomination but whether this pressure was real or imagined is difficult to know. What can be known is that the changing demographics of the town “interfered with regular progress” (The Witness, June 11 1881). The community had become unsettled in anticipating the change of leadership.

He was called back to Halifax by Chalmers Church in 1881 but was pressured to stay in Little Bay longer and “complied with the wish of the Board to remain for another year” (The Witness, June 11 1881). This led him, at the end of his mission in Newfoundland, to write with his characteristic sass “My second year of service within the bounds of Newfoundland Presbytery and under your appointment has been unexpectedly prolonged and so I find is my report” (The Witness, June 17 1882). Whittier busied himself with social events. On the 11th of November 1881 he married mine captain Philip McVicar to Elizabeth Crane. This event was a big deal. His church was “brilliantly illuminated for the occasion and which, with its usual unique appearance, presented an attractive spectacle” (TS). In February of 1882 the Little Bay Choral Society hosted its first concert at the public hall. Rev. Whittier participated by doing a reading (TS).

During his last year his letters take on an increasingly defensive stance and he seemed to believe that his work was being unfairly judged. He wrote “Let me plainly say that after five years operations we have very little to show [but] a failure it is not by any means” (The Witness, June 17 1882). He explained that his situation was exceptionally difficult. “Almost every week during summer familiar faces disappear from our little commonwealth of 2000. [. . .] One must act the recruiting agent to search out and enlist, be on the lookout everytime a steamer comes in, keep up a revised knowledge of all boarding houses, and go over the pay sheets of the company every month [. . .] Prospecting parties [. . .] cut into the bush for months, and must needs be followed by letters and papers in person.” During his stay he “travelled in boots and boats through the northeastern regions over 10,000 miles, or an average of 96 miles a week during all seasons for two years” (The Witness, June 17 1882).

Rev. McNeill also pointed out that Whittier had worked under difficult conditions. “The isolation of the population, the number of mining centres, fluctuation of the people, the paucity of settled families, the uncertainty resulting from negotiations for the sale of the mining property, the final change of companies, and the consequent change of officials and leading men, have all rendered [his] position very unsatisfactory” (The Witness, Feb 18 1882).

Whittier’s farewell letter to the town contains some curious lines such as “Knowing how fractional my work has been and how liable to be misunderstood, I am specially gladden to have your approval” and “my conviction is that no man can be true to the best interests of any Church or any cause who is not ready to respect the honest opinions of others” (TS June 16 1882). Taken in context these lines reflect the type of stress he was feeling from external pressure. It does not seem to have come from inside the town as Rev. Whittier wrote to thank “the managers who generously made their home my own during my entire stay ; to the officers of the Company without exception for uniform courtesy and considerate favours” . Furthermore, he pointed out “how mutual helpfulness [was] better than contention” . He hoped that the existence of denominations would come to pass and asked that it be “remembered that when our cause leaned upon the general protestant community that community generously carried it aloft” (The Witness, June 17 1882).

Whittier’s farewell letter to the town contains some curious lines such as “Knowing how fractional my work has been and how liable to be misunderstood, I am specially gladden to have your approval” and “my conviction is that no man can be true to the best interests of any Church or any cause who is not ready to respect the honest opinions of others” (TS June 16 1882). Taken in context these lines reflect the type of stress he was feeling from external pressure. It does not seem to have come from inside the town as Rev. Whittier wrote to thank “the managers who generously made their home my own during my entire stay ; to the officers of the Company without exception for uniform courtesy and considerate favours” . Furthermore, he pointed out “how mutual helpfulness [was] better than contention” . He hoped that the existence of denominations would come to pass and asked that it be “remembered that when our cause leaned upon the general protestant community that community generously carried it aloft” (The Witness, June 17 1882).

Rev. Whittier experienced Little Bay during a complicated point in its history. The culture was in a state of transition. The departure of the German leadership was stressful for everyone. Rev. Whittier requested that a Presbyterian presence remain in Little Bay for another year to assist the people there with that transition. It was important to him that a Presbyterian “minister should be at his post when new miners and managers [came] on the ground” (Acts and Proceedings). Rev. McNeill furthered this position and thought it “necessary for the Board to secure a good man for Little Bay without delay. The place cannot be left unoccupied” (The Witness, Feb 18 1882).

Fitzpatrick

Rev. James R. Fitzpatrick was Little Bay’s last Presbyterian and the one I know the least about. However, what I have put together is fascinating. If Rev. Gunn can be said to have aided the Baron in creating the sense of community in Little Bay and Rev. Whittier had therefore to experience the consequences of its absence then Rev. Fitzpatrick can be seen as the man the Presbytery sent to make things right.

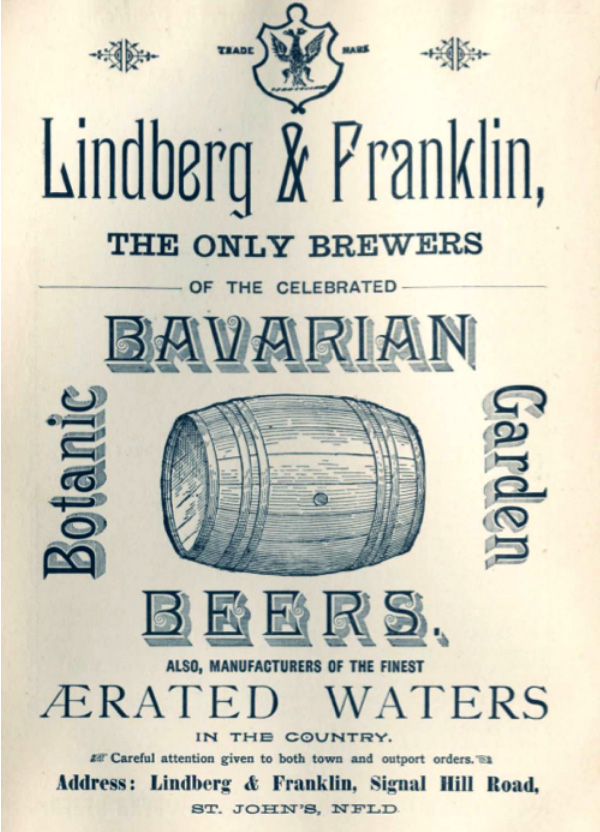

I’ve found no reference to the consumption of alcohol in Rev. Whittier’s writings however it was a focal point of Rev. Fitzpatrick’s effort. It’s difficult to place exactly when the town started allowing alcohol. It’s safe to assume that the Baron had it banned so it likely occurred under the management of E. C. Wallace but I can’t say for certain how much power mine management retained over setting laws after the Germans left. The first reference to alcohol being sold in Little Bay appears in association with Skittle Alley proprietor John Lamb who was present by September of 1883 (TS). It should be noted however that Daniel Henderson, who had worked as a leading man at both Little Bay and Betts Cove claimed that B.B. beer was openly drank by the men at both sites but that one could not become intoxicated by drinking it (Decisions of the Supreme Court 1884). It’s interesting to note that B.B. was a property of James Lindberg out of St. John’s and Lindberg was the owner of the Skittle Alley and John Lamb’s business partner.

John Lamb was quickly targeted by Fitzpatrick. Moncrieff credits Rev. Fitzpatrick with starting Little Bay’s Temperance Movement. Rev. Fitzpatrick took a leadership role in the movement, taking a strong total absence stance (TS). August of 1883 saw the arrival of Sergeant Wells. Wells would turn out to be a staunch ally to Fitzpatrick’s Temperance efforts. It’s from this point forward that the showdowns between police and alcohol sellers are documented. The first mention I’ve found of Little Bay’s Temperance cause is from Christmas of 1883. A public meeting was held at which Rev. Fitzpatrick was the celebrated speaker and Sergeant Wells was praised for laying charges against John Lamb (ET).

John Lamb was quickly targeted by Fitzpatrick. Moncrieff credits Rev. Fitzpatrick with starting Little Bay’s Temperance Movement. Rev. Fitzpatrick took a leadership role in the movement, taking a strong total absence stance (TS). August of 1883 saw the arrival of Sergeant Wells. Wells would turn out to be a staunch ally to Fitzpatrick’s Temperance efforts. It’s from this point forward that the showdowns between police and alcohol sellers are documented. The first mention I’ve found of Little Bay’s Temperance cause is from Christmas of 1883. A public meeting was held at which Rev. Fitzpatrick was the celebrated speaker and Sergeant Wells was praised for laying charges against John Lamb (ET).

Fitzpatrick also took up the cause of literacy left by Rev. Whittier which led to the creation of the town’s Reading Room (Moncrieff). In August of 1883 a Reading Room was opened in Little Bay (ET). The Reading Room began as a book sharing exercise with membership cards but was eventually brought inside when an extension was added to the Public Hall to accommodate it. In letters to the editor of the Twillingate Sun the cultural value of this Reading Room was held in stark contrast to the game of Cricket. Cricket was also new to Little Bay. The game arrived from St. John’s with John Lamb. I believe what happened was that as Lamb brought legal alcohol to Little Bay along with the games of Skittles and Cricket those games took on the social scorn directed at him by the Temperance crowd. It didn’t help that cricket matches would often host rival towns and ended at bonnet hops which were public dances that could go on late into the night. The population was heavily supportive of cricket and the games were well attended which likely strengthened resistance to Temperance and the Reading Room. This put Cricket and drinking on one side of a cultural divide with literacy and Temperance on the other. Together this set the stage for a cultural split that would eventually end in arson. However, on a more positive note the Reading Room and Temperance Movement would remain stables of Little Bay’s culture for years with literacy and Temperance often found associated together in later references. A combination that I believe greatly aided the empowerment of women in Little Bay and also result in Little Bay’s boasting when eventually every house in the town could claim a bookshelf.

In the spring of 1884 Rev. Fitzpatrick “was encouraged by the increase in Sunday School attendance [and] the community was prosperous. There was work for all and no need for poverty in the town. However, the majority of the Protestants [. . .] were now Episcopalians.” As there was no longer any reason for his presence Rev. Fitzpatrick left town in June of 1884. This closed the Presbyterian church (Moncrieff). The building remained and was afterward used by the Methodists. Christ’s Church was eventually moved from Betts Cove to Little Bay where it became the town’s Public Hall and hosted many high-cultural events. The spire from it ended up adorning Little Bay’s Episcopalian church (Ohman). The spirit of multi-denominational community that the Presbyterian church had represented meant that it could not have been put to better use. The Presbyterian influence was felt in the community for years beyond the presence of its clergy. In 1892 the visiting Rev. Lumsdon praised Little Bay for its unusually supportive approach to a multi-denominational culture. He may not have known what had set Little Bay’s culture apart then but I think I do now. It was a cultural legacy left to the 19th century mining town by a German Baron named Franz von Ellershausen and a Presbyterian Reverend named Archibald Gunn.

In the spring of 1884 Rev. Fitzpatrick “was encouraged by the increase in Sunday School attendance [and] the community was prosperous. There was work for all and no need for poverty in the town. However, the majority of the Protestants [. . .] were now Episcopalians.” As there was no longer any reason for his presence Rev. Fitzpatrick left town in June of 1884. This closed the Presbyterian church (Moncrieff). The building remained and was afterward used by the Methodists. Christ’s Church was eventually moved from Betts Cove to Little Bay where it became the town’s Public Hall and hosted many high-cultural events. The spire from it ended up adorning Little Bay’s Episcopalian church (Ohman). The spirit of multi-denominational community that the Presbyterian church had represented meant that it could not have been put to better use. The Presbyterian influence was felt in the community for years beyond the presence of its clergy. In 1892 the visiting Rev. Lumsdon praised Little Bay for its unusually supportive approach to a multi-denominational culture. He may not have known what had set Little Bay’s culture apart then but I think I do now. It was a cultural legacy left to the 19th century mining town by a German Baron named Franz von Ellershausen and a Presbyterian Reverend named Archibald Gunn.