Buildings are strange and social things. Churches have especially complicated relationships. Little Bay’s Catholic church and its first priest are entwined. Their relationship exemplifies this project as a whole.

Buildings are strange and social things. Churches have especially complicated relationships. Little Bay’s Catholic church and its first priest are entwined. Their relationship exemplifies this project as a whole.

I uncovered this story slowly, piecing it together from forgotten documents and half remembered tales, from once living people and events nearly lost to time, from uploaded images and unexpected archives.

Little Bay is history forgotten. This is a ghost story that haunts the corners of places once material but now largely digital. It survives in newspapers uploaded but unread. It survives in the background of old photographs. This is a tale tucked away as a shadow in the background of other things.

I’ll start by telling you a forgotten name. It was called “Her Lady of Carmel Parish” and it sat atop a hill overlooking Little Bay from 1881 until its destruction by fire in 1905. The tale starts closer to the beginning of the town though, in Little Bay’s second year, in the year 1879.

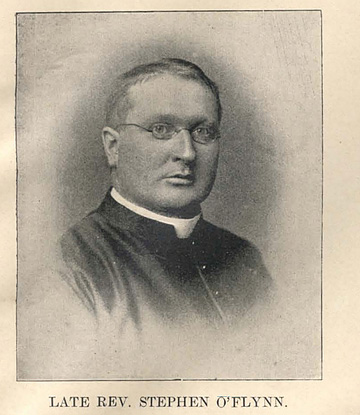

Little Bay’s first Catholic priest arrived that year, his name was Stephen O’Flynn and he was among the first of the town’s clergy. Father S. O’Flynn was 28 years old. References to him appear alongside the Reverend Arthur Pittman from the Church of England but not before the town’s first religious leader: a Presbyterian Reverend by the name of Archibald Gunn.

Rev. Gunn was fundamental in setting the stage for the interplay between the town’s denominations and like all of the original leadership was likely appointed by Baron Francis von Ellershausen himself. In the beginning the town was primarily Presbyterian and like much of Little Bay’s early culture, this was by the Baron’s design. Baron Ellershausen made sure the first church was from his and his German workers denomination.

I’ve been so far unable to name the Presbyterian church which was likely floated over from Bette’s Cove along with most of Little Bay’s early structures by the original German population. During the first years it was the town’s only church and it functioned as a shared space which welcomed worshippers from the three resident faiths. Rev. Gunn, in opening his church to the other religions demonstrates a working relationship between the three ministers. They worshipped together and what few records I have of their cooperation appear quite cordial. This early environment of religious tolerance I believe can be credited to the work of the Baron and his appointed clergy, Rev. Gunn. Working together with such men to create an accepting and diverse community likely informed S. O’Flynn’s own community efforts. In fact, by all diary accounts, Father Stephen O’Flynn maintained deep friendships with much of Little Bay’s Protestant leadership for the rest of his life.

Little Bay was divided into several districts with the largest two named The Bight and Loading Wharf. Her Lady of Carmel Parish sat on the hill which divided those districts and eventually shared the hill with The Church of England’s St. Luke’s. In 1881, however, when construction began on Her Lady of Carmel Parish, it was to be the town’s second church. The building would take nearly two years and was not completed until 1883.

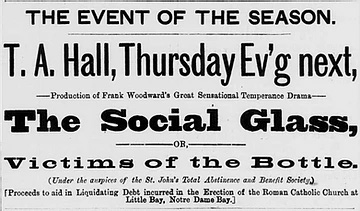

Throughout the late 19th century there was a give-and-take relationship between St. John’s and Little Bay in regard to fundraising with each helping the other’s population in times of need, in particular after their disastrous fires. In that tradition, the final money for Little Bay’s Catholic church was collected in St. John’s by way of public performances in 1885.

Throughout the late 19th century there was a give-and-take relationship between St. John’s and Little Bay in regard to fundraising with each helping the other’s population in times of need, in particular after their disastrous fires. In that tradition, the final money for Little Bay’s Catholic church was collected in St. John’s by way of public performances in 1885.

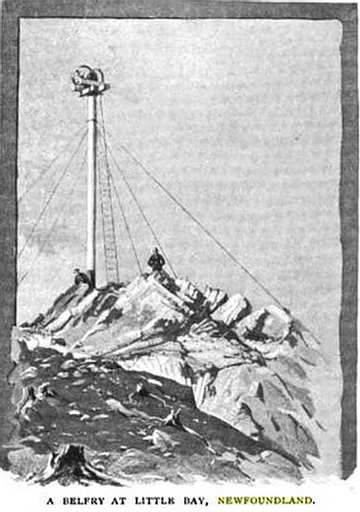

Unlike its neighbour, St. Luke’s, Her Lady did not have a bell tower but claimed a belfry instead. This belfry was noteworthy and was drawn during the visit of an adventurer named Gustav Kobbe who published his account of Little Bay in an American boy’s adventure magazine in 1894 along with the drawing of the belfry. The belfry was held with black iron eyebolts, they are all that remain to mark the place where once Her Lady stood.

The bell for Her Lady’s belfry was poured in the town itself. I believe it was likely the work of the blacksmith John Conway. The oral history told that the townsfolk tossed silver and copper coinage into the molten metal during its formation. To picture that, the residents feeding the bell with their own hard won wages, depicts a product of a living town.

The bell for Her Lady’s belfry was poured in the town itself. I believe it was likely the work of the blacksmith John Conway. The oral history told that the townsfolk tossed silver and copper coinage into the molten metal during its formation. To picture that, the residents feeding the bell with their own hard won wages, depicts a product of a living town.

The bell was named St. Patrick and in 1889 it fell and was broken into twenty pieces only to be recast the very next day. They must have felt pride to hear it ring. The storied bell, imbued with the power of folktale, was said to be heard ringing for miles away. That bell is one of the few items that survived the fire and it currently resides in the Catholic church in the aptly named St. Patrick’s, the neighbouring town which itself was once a district of Little Bay.

A church can die because churches are living things. They exist beyond wood and mortar. Her Lady connected memories rich with shared emotion. The man that worked from Her Lady of Carmel Parish, Father S. O’Flynn, was a community and cultural organizer. Aside from the usual church functions of Mass, Christenings, Weddings, and Funerals, Little Bay’s Catholic community held a weekly Bazaar.

The evening of the Bazaar started with a parade. Little Bay’s Brass Band would head the parade led by band leader Lynch on his clarinet. A column composed with the whole of the town’s nearly 300 children followed the band to the Bazaar to mark its weekly opening. This paints a lively image of a town rich with sound.

Father O’Flynn also organized significant cultural events such as picnics and festivals. Many of these would be interdenominational and involve the whole population of the town. Much of the people’s most meaningful and significant life events were housed in the churches. The people of Little Bay would have looked up at Her Lady and remembered, upon seeing it there, the most important moments of their lives; the welcoming of new babies, the celebration of their marriages, and the grieving they did for parents, partners, and friends. For the faithful it was further a holy place and the man who oversaw its rituals and ceremonies was held in awe. The position afforded him respect but also a high level of material comfort.

Father S. O’Flynn’s house was under construction immediately following the completion of the church. In 1883, due primarily to fundraising from the Bazaar, it was finally displayed luxuriously for all to see. It was described as one of the most beautiful homes in town and supported a sizeable and well kept grounds. The house was tended by a housekeeper named Bridget Leary. It stood next to the manmade pond which housed the upper class’ pleasure crafts. Father O’Flynn’s ship The Shanondithid was a regular winner of Little Bay’s races and placed first in the town’s 1887 regatta. Constable Meany manned the vessel in that race from Little Bay to Little Bay Islands and back. S. O’Flynn cheered from the shore with the rest of the townsfolk.

By the mid 1880s Her Lady of Carmel Parish took centre stage as Little Bay’s German population had largely left, altering the town’s religious makeup. The majority of the population were now Roman Catholic and English speaking. This demographic more closely reflected the rest of Newfoundland. There is little religious animosity recorded in the town in the early years but there appears to be a shift in tone by 1886 when a sign reading “No Papists need apply as only genuine Protestants are required in this job” was placed on the mine leading to a police investigation. Tensions ran even higher with regard to the Salvation Army after their arrival in 1889 as I’ve depicted in a previous article. However, there are many records speaking to cooperation between the town’s religions and few records of hostility.

By the mid 1880s Her Lady of Carmel Parish took centre stage as Little Bay’s German population had largely left, altering the town’s religious makeup. The majority of the population were now Roman Catholic and English speaking. This demographic more closely reflected the rest of Newfoundland. There is little religious animosity recorded in the town in the early years but there appears to be a shift in tone by 1886 when a sign reading “No Papists need apply as only genuine Protestants are required in this job” was placed on the mine leading to a police investigation. Tensions ran even higher with regard to the Salvation Army after their arrival in 1889 as I’ve depicted in a previous article. However, there are many records speaking to cooperation between the town’s religions and few records of hostility.

The Catholic church oversaw much of the town’s education. Little Bay had four schools at its peak with two of them Catholic. One Catholic school was located in The Bight and the other at Loading Wharf. There were at least 150 Catholic children in total with 100 of them enrolled in the school in The Bight under Mr. Hanrahan.

Father S. O’Flynn was involved in the community in a variety of ways. Most notably he was an active member of the town’s Temperance Movement, but he was further involved in fundraising for fire relief, meetings concerning the French Shore, and he was a member of the community Road Board. Little Bay’s Roman Catholic congregation would ascend a long and narrow staircase to their church and would have had a grand view of both sides of the town and its harbours. There were some issues raised with the safety of the stairway to Her Lady however, which fell under the road board’s jurisdiction. The townsfolk were unhappy with the staircase and petitioned to have it replaced. The problem was not remedied promptly so late one night they destroyed it to force the issue. Their vandalism worked and it was replaced with a safer set of stairs.

Besides preaching to the congregation at Her Lady of Carmel Parish S. O’Flynn would regularly travel the island by steamship and once did missionary work in Labrador, leaving Little Bay for several months in an effort to convert the Inuit there.

Besides preaching to the congregation at Her Lady of Carmel Parish S. O’Flynn would regularly travel the island by steamship and once did missionary work in Labrador, leaving Little Bay for several months in an effort to convert the Inuit there.

Father O’Flynn died in St. John’s after a carriage accident in 1899 at the age of 49. Her Lady did not last long without him. Her Lady of Carmel Parish’s first and founding priest Father Stephen O’Flynn left an imprint and his name was known across the island.

After his death a short write up about him was included in a Christmas magazine, which is where I stumbled upon his picture. It was a lucky discovery as previous publications on the history of Newfoundland priests were unable to find a picture of the man. I’ll admit to a little researcher pride at being able to email the church his image.

His legacy seems to have transformed into myth for the first half of the 20th century. Like his church he was imbued with the power of folktale. Into the 1960s he was claimed a miracle worker and capable of such feats as lighting matches in the wind that wouldn’t blow out. By the end of the 20th century, however, both he and the church he’d created were lost to living memory. Lost that is, until, piece by piece, they started to haunt hidden corners online. It is only by the oddness of this historical moment that I’ve been able to piece together their story.

Her Lady came under new leadership as S. O’Flynn was replaced by Father John J. Lynch who was responsible for burning down the town in 1905. An accident which started while he was cooking at night. His ceiling caught fire and the whole of the town was consumed in a matter of hours. This marked the death of Her Lady only six years after the loss of its founding priest. It appears that much of the RC documents were destroyed in that fire as well.

Her Lady came under new leadership as S. O’Flynn was replaced by Father John J. Lynch who was responsible for burning down the town in 1905. An accident which started while he was cooking at night. His ceiling caught fire and the whole of the town was consumed in a matter of hours. This marked the death of Her Lady only six years after the loss of its founding priest. It appears that much of the RC documents were destroyed in that fire as well.

Little remains of Her Lady of Carmel Parish. I have climbed the hill to where it stood and found only the black iron eyebolts that held its belfry. What few images of the building I’ve located are included here, hazy and unfocused, it was hidden in the background of other things. This story is composed of forgotten corners.

Churches may live and die but Her Lady found an afterlife of sorts online over one hundred years after it was destroyed. This is a modern haunting: a digital haunting. The alter and bell were moved to the church in St. Patrick’s and Her Lady’s old cemetery is still there on the hill but it is no longer in use.

It has been an odd journey uncovering this story, the love of a town for its priest and his church. Theirs is a pairing that survived once as myth until forgotten, only then to resurface in pieces of media online, from where I could recovered them bit by bit and herein resurrect.

Thank you for reading!