I’ve decided to explore the history of the Little Bay mine itself in this piece. However, I didn’t want to tell it from the perspective of the owners or managers and instead opted to focus on the experience of the mine from the point of view of the miners. It is perhaps an impossible task as their voices are little recorded but nevertheless I’ve done my best to showcase them here. Little Bay was its people and its people mined. Without the industry there was no town and while the Baron may have overseen its construction it was the working men who carried it out. Many of the first miners followed him from Bett’s Cove in 1878, bringing their houses with them and they set to work building the town of Little Bay and its mine in unison. Rev. Moses Harvey describes the scene as he witnessed it.

I’ve decided to explore the history of the Little Bay mine itself in this piece. However, I didn’t want to tell it from the perspective of the owners or managers and instead opted to focus on the experience of the mine from the point of view of the miners. It is perhaps an impossible task as their voices are little recorded but nevertheless I’ve done my best to showcase them here. Little Bay was its people and its people mined. Without the industry there was no town and while the Baron may have overseen its construction it was the working men who carried it out. Many of the first miners followed him from Bett’s Cove in 1878, bringing their houses with them and they set to work building the town of Little Bay and its mine in unison. Rev. Moses Harvey describes the scene as he witnessed it.

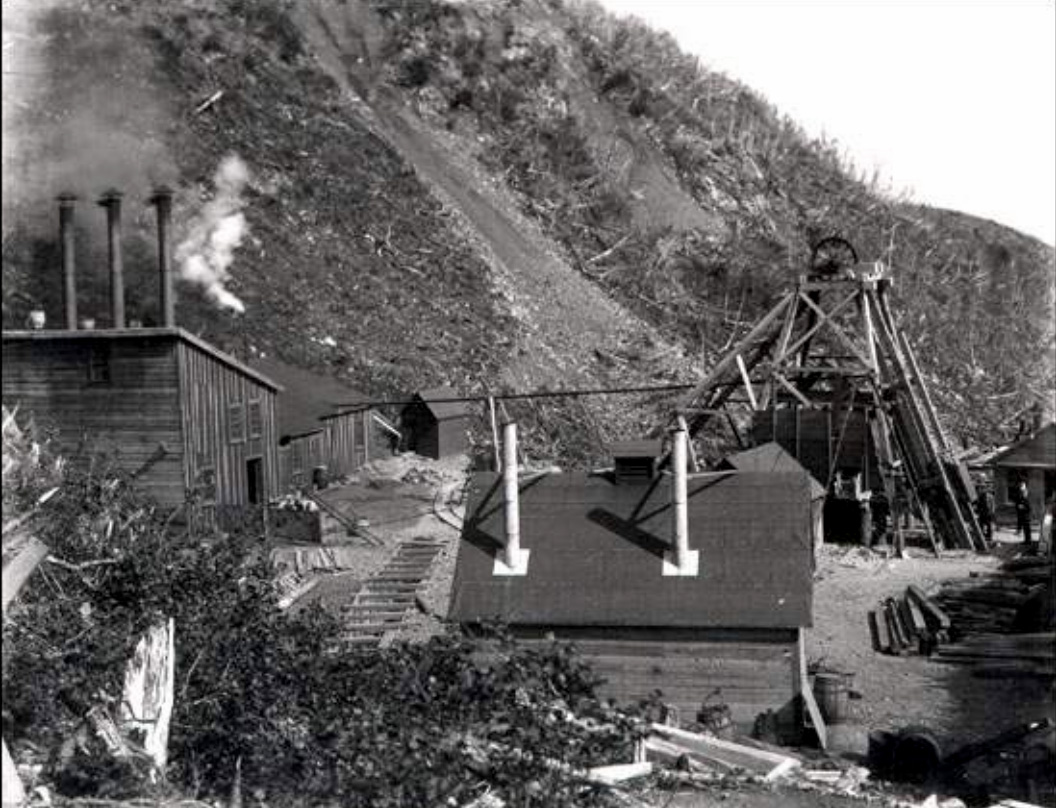

“We landed at the harbour of Little Bay, where we found two vessels loading copper ore. Six weeks previously not a human being was to be seen near the spot. The stillness of the woods unbroken by any human sounds. Now five hundred and twenty stalwart miners were quarrying the ore of Copper Cliff. A tramway nearly a mine in length connected the mine with the harbour; houses, stores, and a wharf were built; 3,000 tons of ore were shipped, and 6,000 tons of rock had been removed. [. . .] All of this — incredible as it may seem — was the work of six weeks. Our party walked along the strongly-built tramway and spent an hour examining the mine and wondering over the great blocks of ore brought down from the cliffs” (Harvey).

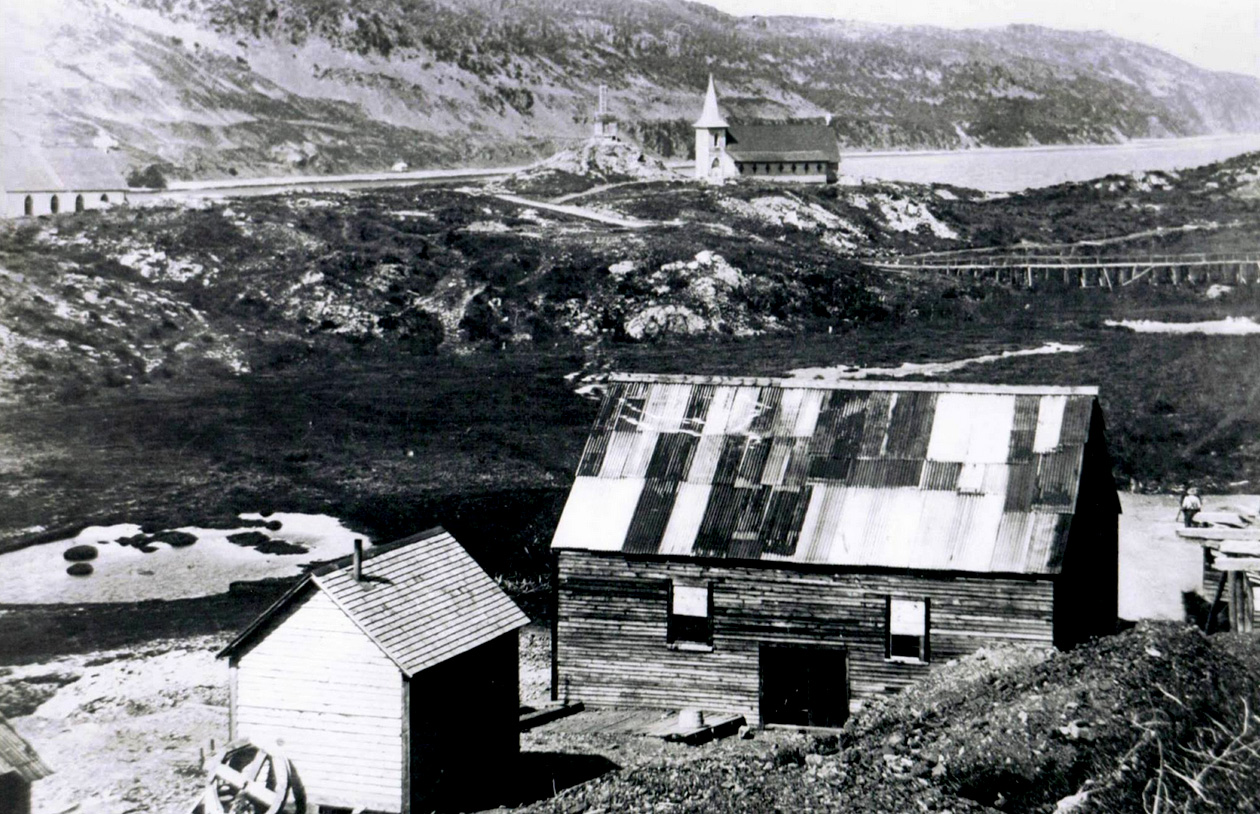

Little Bay was now a town of several hundred “with a mile of tramways, shaftings, copper floors, washing machinery, smelting furnaces [. . .] where a little over a year ago the unbroken forests of fir, birch, and pine grew down to the water’s edge, and the first mark of civilization had not been made” (HGS / L. C. MacNeill). It was recognized immediately as a powerful new stimulus. Newfoundlanders took courage from the “indications of mineral wealth, to predict that the future glory of Newfoundland [would] not be in her rich fisheries but in her exhaustless mines” (STNA&PO).

James Howley paints a similar picture in returning to a place he’d been recently to find civilization where only months before there’d been wilderness.

“A large force of miners were engaged attacking the mine Bluff which they had completely honeycombed. Blasts were going off day and night resembling a park of artillery in action, and indeed it was dangerous to approach too near. Rocks from the blasts were flying in all directions. The swamp which had existed close in front of the Bluff had been drained and filled up with debris from the mine, and now a large extent of dry level land appeared. Many hundreds of tons of fine ore were piled up upon this level, being dressed and cleaned for transportation to the pier. The whole presented a scene of utmost activity. This then was the commencement of the celebrated Little Bay Mine which subsequently developed into one of the greatest mines in the island. Already they had raised some 10,000 tons of ore, and during the years following, Little Bay Mine contributed a large portion of our annual Copper output” (Howley).

Deaths

The Evening Telegram notes Little Bay mine’s safety record in 1896 by pointing out that there were only 8 mining deaths there in the previous 15 years. Only two of them from falling rock. I was hoping I could find them all and list the names of lives lost to the mine but I fell short. I have found 7 deaths between 1881 and 1893. I’ve found 3 more in the years 1879 and 1880 which precede that 15 year mark. It seems likely I’m missing someone. I have found 10 deaths in total. Of those only 9 names and of those only 8 full names. Nevertheless I will name them for you: George Moores, James Fahey, Nicolas J. Cantwell, Peter Signott, William Garman, Luke Madden, William Maddigan, John Appleton, Mr. Young, and an unnamed man from Little Bay Islands.

The Evening Telegram notes Little Bay mine’s safety record in 1896 by pointing out that there were only 8 mining deaths there in the previous 15 years. Only two of them from falling rock. I was hoping I could find them all and list the names of lives lost to the mine but I fell short. I have found 7 deaths between 1881 and 1893. I’ve found 3 more in the years 1879 and 1880 which precede that 15 year mark. It seems likely I’m missing someone. I have found 10 deaths in total. Of those only 9 names and of those only 8 full names. Nevertheless I will name them for you: George Moores, James Fahey, Nicolas J. Cantwell, Peter Signott, William Garman, Luke Madden, William Maddigan, John Appleton, Mr. Young, and an unnamed man from Little Bay Islands.

Many of the deaths happened when someone slipped and fell into an open shaft. I should warn you these are often reported graphically. In 1880 a man named John Appleton died by falling down one of the shafts (TS, CH). Another man, named William Maddigan died the same way later that year (TS). On December 10th 1890 Nicolas J. Cantwell died while coming off the nightshift. He was the last man coming out by the ladder when he “lost his hold and fell about 300 feet down the shaft. His body was found shortly after in a broken condition with his face downward. Portions of his body were found in different parts of the shaft” (ET). In October of 1887 Peter Sinnott fell from a ladder near a shaft. He had been making hoisting preparations when his “ladder gave way, causing him to fall down the shaft, over six hundred feet. Death was instantaneous. His brains were dashed out, skull fractured, and leg, back and neck broken. Sinnott was one of our foremost and typical Newfoundland miners, a native of Placentia, and aged 37 years. He [left] a wife and three children. His death [threw] a gloom over the community” (ET).

The earliest mining death I’ve found occurred on May 10th 1879. “A man named Young, of Bay Roberts [was killed] by collision of a loaded car which ran from the track into an empty one, which he had been watching. Poor Young [left] a wife and three children” (CH). Young’s death gives a small glimpse into the technology being used to move the ore. The next death reported describes the car system in greater detail. An unnamed man from Little Bay Island died in the mine on August 13 1881. It was the custom that before the cars started downward to give the man operating the breaks notice. The cars travelled by gravity so the brakeman kept them from crashing. The brakeman was on his dinner break when Mr. Young set the car in motion. The car picked up speed as it went. This caused another car to come up the ramp at the same speed. The miner caught his mistake but not soon enough. He tried to stop the car by springing the line but tripped over the wire and was struck by the car. This “broke his leg at the ankle, crushing it to pieces above the knee. And a piece of iron belonging to the car, made a hole in the poor fellow’s body” (ET).

The other repeating cause of death is by having things fall on you while you’re working below. In September of 1886 William Gorman from Harbour Main was fatally wounded “by a hammer falling from the hoisting tub, a distance of one hundred feet. His skull was fractured and he was insensible for seventy-two hours. Death took place [the following] morning” (ET). Late on the night of February 28th 1884 William Conway was wheeling a tram when it tipped and dropped rocks into a shaft. They fell “about 80 feet, where some 7 or 8 men were working. Some of the stones fell on Luke Madden breaking his leg in several places from the knee down, mortally wounding him” (Wells). The victim’s brother, John Madden as well as the miner William Conway blamed the event on negligence claiming that there were not enough railings in place to prevent stones from falling. Constable Wells took a statement from mine overseer William Foran who claimed it “to be quite safe, the shaft protected with two rails and the manhole six feet from the wheelbarrow” (Wells). This safety investigation might have been superficial, but there was a safety investigation. This fact in concert with the boast over the low numbers of deaths speaks to some attention to a safe work culture.

The other repeating cause of death is by having things fall on you while you’re working below. In September of 1886 William Gorman from Harbour Main was fatally wounded “by a hammer falling from the hoisting tub, a distance of one hundred feet. His skull was fractured and he was insensible for seventy-two hours. Death took place [the following] morning” (ET). Late on the night of February 28th 1884 William Conway was wheeling a tram when it tipped and dropped rocks into a shaft. They fell “about 80 feet, where some 7 or 8 men were working. Some of the stones fell on Luke Madden breaking his leg in several places from the knee down, mortally wounding him” (Wells). The victim’s brother, John Madden as well as the miner William Conway blamed the event on negligence claiming that there were not enough railings in place to prevent stones from falling. Constable Wells took a statement from mine overseer William Foran who claimed it “to be quite safe, the shaft protected with two rails and the manhole six feet from the wheelbarrow” (Wells). This safety investigation might have been superficial, but there was a safety investigation. This fact in concert with the boast over the low numbers of deaths speaks to some attention to a safe work culture.

It appears that not all mining deaths attracted equal attention. I have only an obituary listing for a James Fahey killed at Little Bay mines in 1891. Little Bay mines could refer to the town but the use of the word killed makes me think this was a mining accident. Finally, and without any media coverage, the Vital Records lists the cause of death of a resident named George Moores in August of 1893 as a mining accident. His death’s complete absence from the newspapers feeds my suspicion that the deaths I’ve managed to list here are not all of them.

Accidents

From the events described in the deaths we get glimpses of the work being done underground. That presented me with an interesting resource for seeing the mine from the perspective of the men working inside it. So to expand from that I’ve dug up descriptions for other accidents that occurred there.

From the events described in the deaths we get glimpses of the work being done underground. That presented me with an interesting resource for seeing the mine from the perspective of the men working inside it. So to expand from that I’ve dug up descriptions for other accidents that occurred there.

Two accidents took place in March of 1882. The first occurred when a tub fell to the bottom of the shaft. “John Cleary of Brigus had his skull fractured; two other men had their hands hurt” while the second occurred when John Tobin “while foolishly drilling out a miss hole, had his left hand so injured that amputation above the wrist was deemed necessary. Also, John Griffen had his eyes scorched by the same accident” (TS). In July 1882 mine captain John R. Stewart “and two of his men were injured by accidents” (ET). On the 20th of October 1884 two men narrowly escaped death. Israel Locke saw that a rock under which he and Stanley Taylor were working was about to fall. He jumped to a safe distance and called out to Taylor. “Before the poor fellow had time to move, the rock struck him, breaking his leg and thigh. Dr. Henderson was speedily in attendance” (TS).

On Thursday, February 17th, 1886 Joseph Goudie was digging burning ore out of a pile heap when a mass of it fell onto his legs. His left foot was burned off and the poor man was burned “up to the hips on both sides, the clothes having caught fire immediately” (Wells). The Doctor operated on the man for four hours, removing his leg. They did their best to keep him comfortable with chloroform and morphine but he died the following day. Constable Wells and Magistrate Blandford investigated the event and found it had been accurately reported to the authorities.

On February 27th of 1887 “a young man named Louther broke his leg in the mines” (TS). In July that year Henry Hunt was blinded in an explosion. “He was an industrious, steady fellow, and a good deal of sympathy [was] felt for him by those who were employed with him” (TS). In January of 1888 Benjamin Parsons was hurt while helping to remove “a large boiler weighing about 7 tons [and] John Osborne broke one leg owing to a fall which he had in the mines. He fell about sixty feet” (TS). October 1890 saw a young miner named Selby injured by a falling stone which landed on his head. “Dr. Joseph’s medical skill was quickly brought into requisition” (TS). In 1899 Pat Cleary was sent for surgery at Battle Harbour with plans to send him to New York for further medical help after an accident involving dynamite left “him blind in one eye and nearly blind in the other” (Among the deep sea fishers vol 76 1979).

Technology

The miners had hard jobs but highlighting the accidents risks making it sound even more dangerous than it was. The men had safety equipment and a safety record. They had an 8 hour work day. Working animals likely had it worse. Horses were used for mining work in Little Bay. I suspect most were kept underground permanently as Ohman noted the surprise the town’s children expressed at seeing one. Concerns raised over the treatment of horses being shipped to the town was noted and the Twilligate Sun in 1885 and contributed to the formation of Newfoundland’s SPCA.

The miners had hard jobs but highlighting the accidents risks making it sound even more dangerous than it was. The men had safety equipment and a safety record. They had an 8 hour work day. Working animals likely had it worse. Horses were used for mining work in Little Bay. I suspect most were kept underground permanently as Ohman noted the surprise the town’s children expressed at seeing one. Concerns raised over the treatment of horses being shipped to the town was noted and the Twilligate Sun in 1885 and contributed to the formation of Newfoundland’s SPCA.

The technology most highlighted by the recorded accidents was the carts or tubs. This system was upgraded in April of 1885 when a skip-road was built. The skip-road was essentially an underground rail system. The work that had previously been done with tubs was thus made easier. Tubs having been “awkward and dangerous contrivances, liable to frequent fouling in the shaft and sources of peril and death to those labouring beneath” (ET).

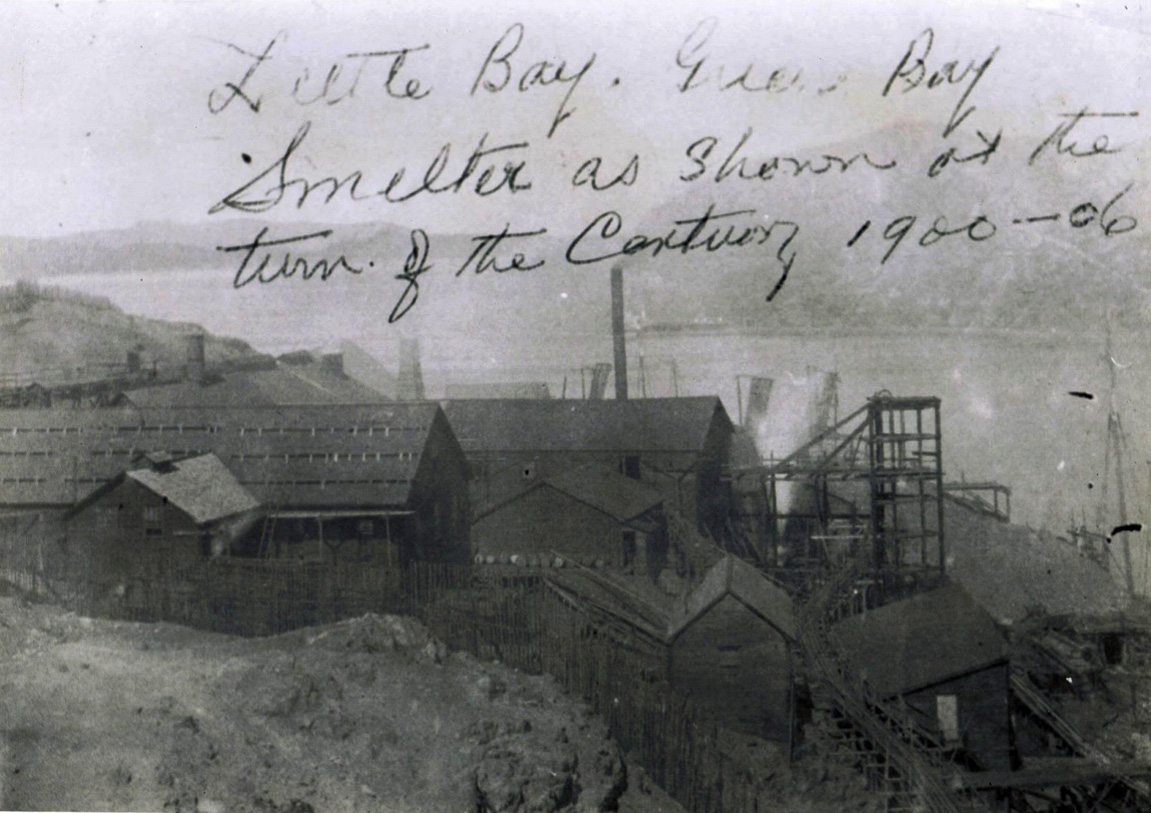

In the summer of 1883 “the first smelters came to Little Bay” (Martin). In April of 1885 “the crusher, jigging mill and smelting house [were] in full swing dressing and purifying the stock of ore lying on the surface” (ET). The smelter was capable “of roasting ore over coal fires to a regulus of 32 per cent copper. In 1887, however, the Consolidated Mining Company installed refining smelters that reduced roasted ore further into copper ingots. The process proved highly lucrative, and from 1887 until 1892 copper ingots formed the mine’s entire output. Miners’ wages rose accordingly” (Martin). The new smelter was expected to “export the copper in its pure state” (Canada a memorial). What shipped from Little Bay after that was said to be the market’s purest copper.

“The result is largely owing to the excellent nature of Little Bay ore ; but not a little praise is due to the untiring activity of the leading smelters. Notably to be mentioned in this connection are Mr. Malephant — who superintended the building of the several furnaces — Mr. Cardwell, of the New Jersey Extraction Works — who remedied the last and only imperfection in connection with the reverberatory refining furnace — and lastly, Mr. Thompson, whose scientific mind detected old impairing causes in the whole process ; and who, from his knowledge of the nature of Little Bay ore, suggested the treatment which is now giving the high percentage of 99.3” (ET 1887).

The smelter was not unstoppable and 1888 saw a shortage of smelting fuel as they could not supply enough coke or coal to run it (TS). Nature also held sway as in1890 when frost stopped the engines (ET). The mine was also continuously filling up with water and the lack of pumps was a topic of contention. One letter to the editor wrote:

“Dear Sir, – I learn that there are now one hundred and fifty feet of water in the Little Bay copper mine. It would be interesting to the people of Newfoundland [. . .] to learn that Mr. E. C. Wallace, the manager there [. . .] contemplate the entire abandonment of this valuable property ; and, if not, why he does not employ a sufficient number of hands to keep the pit free of water. Mining capitalist enjoy peculiar preemptions in this island. Their business is not handicapped here as it is elsewhere with direct taxation. [. . .] As the Betts Cove Mine can keep their mine pumped out there is no reason why the Little Bay management cannot do similarly with theirs” (Evening Telegram, May 26, 1885).

Work

The mine ran for 24 hours a day and I suspect 6 days a week as Sunday was likely a day of rest. The men worked 8 hour shifts with three shifts a day as “any longer time than this would press too severely upon men working at so great a depth” (ET 1889 nov 20). However, while there was some concern for the workmen’s wellbeing, the miners certainly lacked for job security. There were 500 men employed in 1879 (Howley) and 800 by 1881 (Kennedy) but the layoff of 100 men in 1883 resulted in the formation of a union. The workers had a strike in protest and another the following month. This resulted in a meeting where manager E.C. Wallace approved the union and agreed to “give all miners an equal share of the work. The village minister arose next to preach the immorality of preventing one’s fellow man from work” (Martin) It appears they opted to all hurt a little rather than have some hurt a lot. Nevertheless by the end of 1884 many were reportedly at risk of starvation (SJTNA).

The mine ran for 24 hours a day and I suspect 6 days a week as Sunday was likely a day of rest. The men worked 8 hour shifts with three shifts a day as “any longer time than this would press too severely upon men working at so great a depth” (ET 1889 nov 20). However, while there was some concern for the workmen’s wellbeing, the miners certainly lacked for job security. There were 500 men employed in 1879 (Howley) and 800 by 1881 (Kennedy) but the layoff of 100 men in 1883 resulted in the formation of a union. The workers had a strike in protest and another the following month. This resulted in a meeting where manager E.C. Wallace approved the union and agreed to “give all miners an equal share of the work. The village minister arose next to preach the immorality of preventing one’s fellow man from work” (Martin) It appears they opted to all hurt a little rather than have some hurt a lot. Nevertheless by the end of 1884 many were reportedly at risk of starvation (SJTNA).

1885 saw the total number of men employed by the mine dropped to 200 (HGS). Production was slowed drastically for about a year. Work resumed in August of 1885 but slowly. Only a few men were taken on at first so it was unlikely that those who had joined the fishery during the layoff would be able to get back to mining that fall (ET 1885 Aug). By the end of 1885 operations were resumed and there was prospect of upward of 800 men gaining employment. The mining prospects were excellent (HGS 1885 Dec). I have differing employment numbers for 1886 with 1500 men reportedly employed in June (DC) with that number dropping to 600 by November (HGS). Mining boomed on through 1888. The Harbour Grace Standard lists the conflicting numbers of 1100 men and 700 men working that September.

In 1889 Little Bay mine was described in St. John’s as being “twice as deep as the Southside hill is high. The lode of copper leads steadily downward” (ET 1889 nov 20). However, things were not as they appeared and Wendy Martin described the years from1889 to 1898 as lean. There was talk of the operations stopping by January of 1890. Contrastingly, the Colonist claimed that 700 were still employed there that July and the Evening Telegram proclaimed in August that “extensive copper mining operations at Little Bay and Hall’s Bay [were] bringing Newfoundland to the first rank of copper-producing countries” (ET 1890 aug 21).

The reality was that the price of copper had dropped but it took some months before the effect was realized in Little Bay. The summer of 1889 still saw the deepest of the seven shafts employing 400 men. However, the mine’s depth would be its undoing. The crashing rates of copper had “aggravated the already heavy costs of pumping and hoisting in the 1400-foot shaft” (Martin). The highest grades of ore from the upper levels had already been mined out so they’d dug even deeper and with less and less regard for safe procedures. Things got worse when they started removing ore from the pillars that held up the mine. In June 1893 as mining continued “down to the 1420 ft. level and over a length of 600 ft. The Eastern portion of the mine caved, due to pillar robbing” (A pamphlet on the mineral deposits of Newfoundland). The mine cave-in left Little Bay “under a cloud of depression” (The Weekly News 1894).

The reality was that the price of copper had dropped but it took some months before the effect was realized in Little Bay. The summer of 1889 still saw the deepest of the seven shafts employing 400 men. However, the mine’s depth would be its undoing. The crashing rates of copper had “aggravated the already heavy costs of pumping and hoisting in the 1400-foot shaft” (Martin). The highest grades of ore from the upper levels had already been mined out so they’d dug even deeper and with less and less regard for safe procedures. Things got worse when they started removing ore from the pillars that held up the mine. In June 1893 as mining continued “down to the 1420 ft. level and over a length of 600 ft. The Eastern portion of the mine caved, due to pillar robbing” (A pamphlet on the mineral deposits of Newfoundland). The mine cave-in left Little Bay “under a cloud of depression” (The Weekly News 1894).

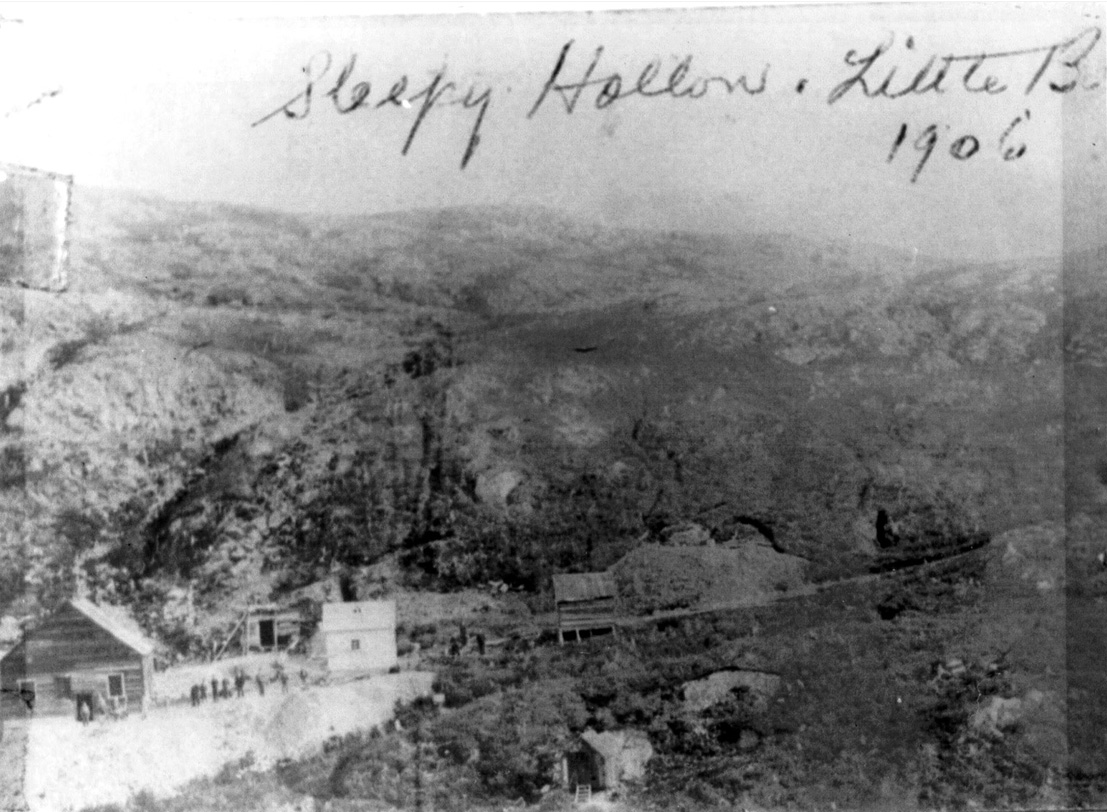

The situation got worse by the day but the newspapers still refused to recognize what was happening which likely means that no one else did either. The Evening Telegram continued to claim that there was plenty of work in its 1892 articles right up until August when it was announced that operations had been suspended. The mine was closed and there was mass unemployment (ET). The mine was stop and go for awhile after that. It was busy in February of 1894 but there was no work that March and it closed again that June (ET). It puttered in fits and starts seeing a brief resurgence from 1899 to 1901 under a changing ownership none of which could afford to keep it in operation. It struggled but never did manage to get back on its feet. Maybe it would have eventually but the fires of 1903 and 1904 saw an end to such lofty visions. By 1905, Little Bay mine, like the great copper cliff that had started it all, was but a memory.

Conclusions

I have two contrasting descriptions of the town in the years that followed. I’ll give you the darker of the two first so as to end on a note of optimism like the miners that remained in Little Bay. Dugin wrote the following of his 1908 visit:

I have two contrasting descriptions of the town in the years that followed. I’ll give you the darker of the two first so as to end on a note of optimism like the miners that remained in Little Bay. Dugin wrote the following of his 1908 visit:

“The deserted mine at Little Bay is a scene of pathetic desolation, indicative of lack of foresight on the part of its managers. It yielded large returns in the beginning; and in their eagerness to gather its riches, and becoming economical as their wealth increased, they neglected necessary precautions to strengthen the mine and it caved. The owners becoming disheartened, it was left, and to-day is a heap of slag, ore, dismantled engine, machines and crushers. Tons of iron lie rusting among the rocks from which the smelter chimney rears its giant shape of bare brick. Back from the scene of the works is a pond with sulphur-stained shores and vacant, weather-worn houses about its banks. Beyond towers the strange brown and green hill, bare of vegetation, a cold, stern, menacing pile, stained with its copper treasure. To the northwest ranges of birch-clad hills rise one above the other, draped with wealths of filmy, curling mist. At my feet were the runs and islands and, way to the north where the run joined the open sea, loomed through the haze of night two weird icebergs, ghostly white. In the west a few bright streaks of dim crimson on the black surface of the pond below. The shadows deepened, silence prevailed and the tenantless houses stood sharply silhouetted against the hills. I thought of the time when this strange place of soundless desolation echoed to the hum of labour, the going and coming of many men, to the blows of hammers, the roar of the stamps, the screams of steam whistles—but this night a dumb ruin in the wilderness” (Dugin).

Dugin is poetic but way too dark so I’ll leave you with this passage from the Newfoundland Quarterly.

“Little Bay is another pretty little mining town, but alas, its glory has departed. It has been scourged by fire, and the last remnant of its prosperity has been swept away. But its inhabitants have invincible faith in its future. Experienced miners say that some day Little Bay will surprise everyone with its copper output. They believe the day is not far distant when its mines will be again in full swing and its yield will exceed that of its palmiest days. Send that it soon may come. Its people are kindly and hospitable, and whoever enjoys the hospitality of Little Bay gets bitten with the fever and longs with its warm-hearted people, that the dawn of better days be not long delayed” (NL Q v 6 1906-1907 P.18).

After the town burned down the dream of restarting the mine was lost to all but the most optimistic idealists. Those are the few who stayed to rebuild the town. The upperclass had mostly deserted the town before things got bad and most of the labourers had also moved on to greener pastures. Many had left before the fire and many more left after it. The population went from 2000 to 200 in short order. A great number of families had moved to Glace Bay in Nova Scotia or to Bell Island to work the mines there. Others had ventured into central Newfoundland to work the new industries in Buchans and Grand Falls. The majority of those who stayed long enough to face the final fires were left homeless and arrived in St. John’s destitute on a ship named the Prospero. The very few who stayed behind to rebuild Little Bay did so on hope alone and for the years between the fire and the first world war they dreamed openly of a coming day when the mine and its prosperity would return to Little Bay.