In the summer of 1886 the St. John’s Daily Colonist sent a reporter to Little Bay. He went undercover. I thought I had found all of his writing from this visit but I recently came across two articles I had not seen. They provided a lot of insight into the mine’s operation. Using those I’d like to take you on a tour by following the ore. It’s an ore-tour!

In the summer of 1886 the St. John’s Daily Colonist sent a reporter to Little Bay. He went undercover. I thought I had found all of his writing from this visit but I recently came across two articles I had not seen. They provided a lot of insight into the mine’s operation. Using those I’d like to take you on a tour by following the ore. It’s an ore-tour!

We’ll start at the bottom. Little Bay’s mine reached 900 feet underground at this time. The miners started their eight hour shifts by descending on wooden ladders. They then toiled away with only candle flames to hold back complete darkness. A miner could use a quarter pound of candles each shift. There were rumours, however, that electric light could soon reach down to them.

They lived at the edge of technological advancement but what new technologies they received were frequently faulty. This subterranean world was still soaked as the pumps preventing flooding were in near constant repair.

In this damp darkness they drew lots to see who would set the blast. When the smoke settled strikers and helpers would set to work breaking the material further apart so that it could be loaded into a skip. A signalling system was then used to communicate with the surface so that the miners needn’t ascend during their shift. The skip was hoisted to the surface powered by steam from above.

An engineer on the surface received a signal to raise the skip. He employs a steam engine to wind a wire rope around a cylinder. As it coils the skip is drawn up to the surface carrying with it the ore from underground, all without anyone having to stop work below. This steam engine is one of three found at the top of shafts. All three are located inside one large building. They are powered there by boilers which run steam throughout by way of a network of pipes. It’s a busy place with workshops filled with tradesmen. Everyone from blacksmiths to carpenters are there making and repairing on-site all the tools necessary for the mine.

From here the ore is dispersed across the dressing floor. A man named Walter Spinney oversees the dressing floor. Here a group of workers composed of men and boys are busy washing and separating the ore. Pieces that are too large are beaten apart with hammers. As quickly as it arrives the ore is off again, dropped through hatches in the dressing floor. Below it we find the start of a half mile of tramway.

The tramway (which I believe was designed by Dr. Eales) is under the charge of Mr. Miller. The ore drops down a hatch and into an awaiting tram-car which waits on the tracks below. Once filled it is set to motion. The tram-car’s next stop is the brake-house found at the top of an incline. The ore-loaded tram-car is lowered by the brake so that it raises an empty one to replace it for the return journey.

Along the route the tram-car passes the stables and the jigging mill. The first is empty because the horses are busy with their own work and the second is empty because the high-tech steam-power ore hammering machine had broken down. The ore next travels around the edge of a pond before arriving at the weigh scale. Here a man is employed to weigh and sample every incoming car before it is sent ahead.

This next part is smokey. A cloud of sulphuric acid hangs over the area. The men who work here are often changed out for their health. The ore must here stop for the roasters. This is done to prepare it for smelting. Sixty tons of ore is placed on a pile of wood. The wood is set ablaze which ignites the ore. This process takes twenty-one days. Afterward it goes to the smelter.

Mr. Malliphant is in charge of the smelter. Many of his men came to Little Bay from New Jersey. They work the furnaces here where it is extremely hot. Out from the smelter pours liquid fire in two streams. One is waste but the other is regulus at as high as 90% copper – this is with an output of forty tons a day! Once cooled it is loaded onto international steamships docked at the loading wharf where operations are overseen by Mr. Burgess. He is responsible for seeing that the ore is safely carried away across the ocean. It will not be unloaded until it reaches its destination at Swansea in Wales. That’s the journey across Little Bay. You’ve now taken the ore-tour up from the bottom of the mine all the way to international waters. I hope you enjoyed the trip.

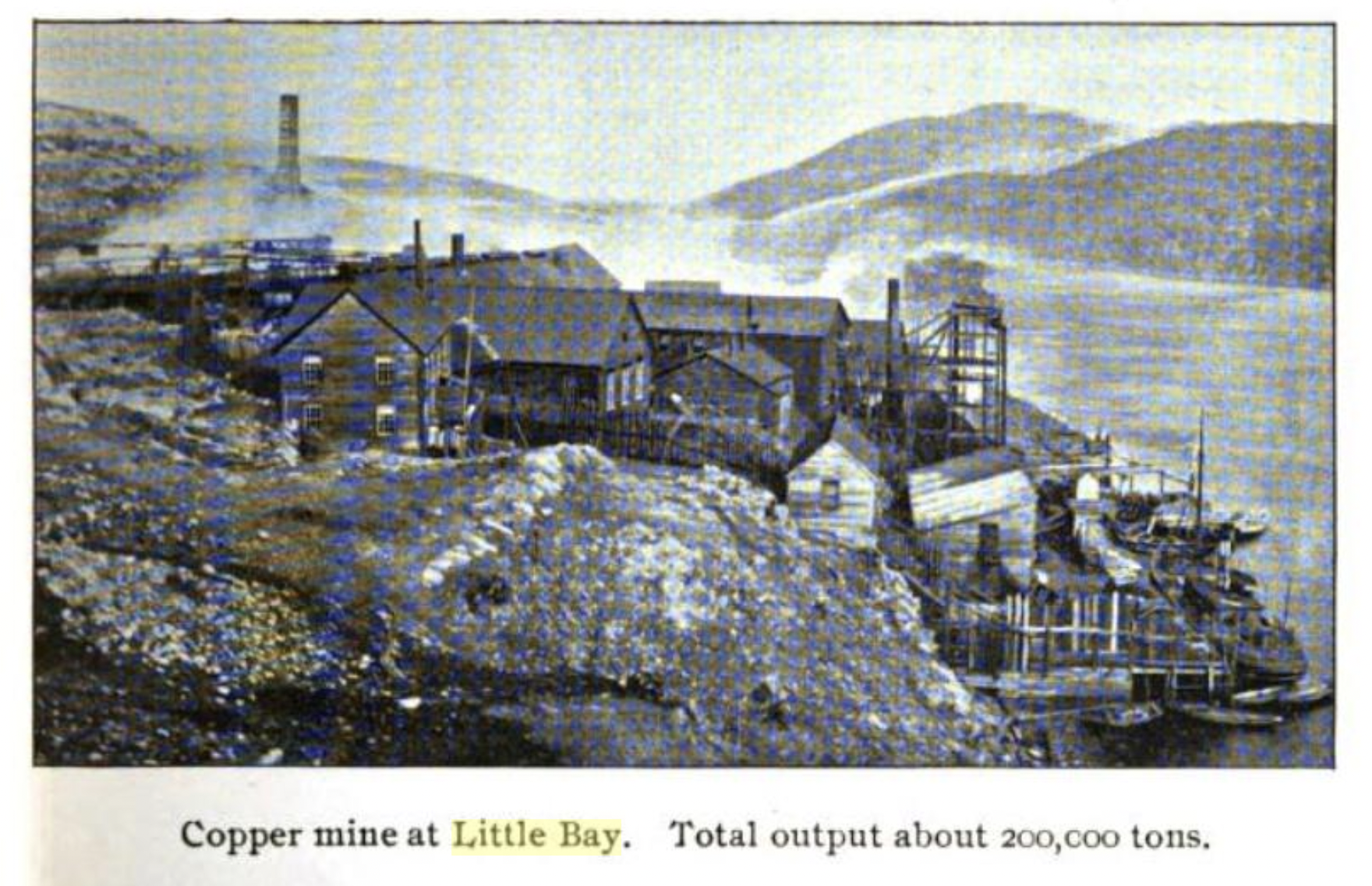

I’ll close by noting that at this time Little Bay’s mine was managed by Mr. Whyte with the help of mine captain Stewart. The images I used show you some of what this looked like. The first is from the Franklin Institute and the last photo I’ve found of Little Bay (it’s rare for me to find new ones these days) and the second was taken by the photographer Mr. Simeon Parsons during his visit. They are both close to the moment in time snapshotted herein (give or take a year).

This is almost all sourced from two Daily Colonist articles dated September 16th and September 20th 1886. The only other info I’ve drawn in were some department head’s names and job details. At some point I’d like to expand on each of the departments mentioned but it’s not likely to be soon. I’ll add it to the list. It’s a long list!

Oh, if you look close at the bottom right of the Franklin photo I think you’ll spot the Hiram Perry. I finally IDed it against a painting I recently found depicting it.

Thanks for reading.