I’d like to address the how and why of my work so if you’re just here for the shaft data just jump ahead to the bolded words. If you do read this one to the end… who knows, you might just get rich!

The Little Bay Heritage Society has asked me to figure out the names and start dates for the shafts of Little Bay Mines for information signs to be placed on their upcoming el Dorado hiking trail which will see its grand opening on August 12th this year (you better come!). I’ll first address the difficulties in fulfilling this request. The fires which destroyed the town in 1903/1904 took with them most of the mine’s documents. This resulted in much missing information such as shaft locations, production numbers, and even underground maps. It was this lack of information which directly lead to the catastrophe in 1965 when then-current mining operations struck a flooded 19th century shaft.

What information remained after the fires consisted mostly of the research conducted by James Howley and M. E. Wadsworth. Later work was conducted by Douglas, Williams, and Rove in 1940. This was all compiled and published by H. J. McLean in 1947. While geological publications follow afterward this largely marked an end to updated historical information about the mine. Those gaps in knowledge carried forward. This is why the production numbers found on Vulcan’s website were the same list found in McLean’s article from back in ’47. Little Bay’s mining claims were held by Vulcan until recently. I met with the CEO of Vulcan Mineral about my findings after noticing this trend. The exception to this trend comes along in 1983 with Wendy Martin’s “Once Upon a Mine” as she managed to track down new original sources in her exceptionally well researched book. Most everything I’ve found published after ’83 pertaining to the history of the mine cites back to either Martin or McLean when you follow their citation trails. I have been in contact with Martin over the course of this project and her work greatly informs my own.

Little Bay mine’s history was not often updated because the known information was what had survived the fires. But, as I keep saying, Little Bay was a big deal. A lot of what was lost can be brought back. The trick, as I’ve figured it, is finding pre-1947 sources which both McLean and Martin missed. This is greatly aided by the fact that so many archives have been digitized online since Once Upon a Mine was published in 1983. The sheer volume of media coverage during the boom years also helps. That has allowed my dataset to get rather massive. Over the passed eight years I’ve been putting every reference to 19th century Little Bay that I’ve found into a program called Tropy to tag them for quick recall. This collection has grown to number thousands of references and includes most newspapers, a few church newsletters, and some original writings.

I had someone recently question my credentials and my right to undertake this work so I’d like to give you a better understanding of my interest, method, and process. My research is hyper-focused on the town of Little Bay itself over a very fixed period – from 1878 to 1904. I think I can claim expertise on that place over those years. I’ve certainly put the work in. That said, I am not from Little Bay and local knowledge helps me correct errors – especially with the 20th century stuff as it’s outside my focus. Nor am I a geologist, a historian, or a folklorist any of which would no doubt bring their own flavour and methodology to the work. I am trained as a social theorist. My degrees are in anthropology and sociology. My academic work has been on the subjects of addiction and seduction. I am interested in the way a person’s agency and their social structures act on each other. It’s Practice Theory if you’re interested.

I came to this project by way of my mother’s genealogy. I got hooked on it quickly and started documenting everything I could about the town’s culture. It’s a microcosm and perfect for understanding the intersection of agency and structure. It is fixed in time and space and supremely well documented. It’s a lost media project containing a whole town! I will probably be at this for the rest of my life. I didn’t start off with aspirations to heritage work but it came naturally out of posting my findings online. I like doing this publicly because it helps to have a community of people to correct my mistakes and contribute sources I wouldn’t otherwise find such as family oral histories, photographs, and original writings.

If you’ve been following my work from the start you’ll notice I first mapped out my Little Bay references by year, next by institution, and now I mostly organize by family name. Structure informs agency and I’m trying to understand the life of the town during this time. At this point when I’m writing about a family I do so with an awful lot of knowledge about what was happening with pretty much every institution there. I know the place usually down to the month and often down to the day. So my database lets me pull a lot of sources together quickly and put events into context.

All that said, while I’ve got the advantage when it comes to covering the town’s culture, it is not easy to find things about the mine that both McLean and Martin missed. They were way more focused on the mining itself and they’re really good at what they do. However, the reason I was talking to Vulcan’s CEO in the first place is because I’ve found production numbers in my archive that are absent, so far as I can tell, in every publication since McLean. And more recently I’ve stumbled upon a powerful new source in the University of Alberta online library – namely The Newfoundland Mining Corporation’s 1881 publication which gives us the exact number of shafts for Little Bay Mine which is something I know McLean didn’t have. So let’s see what we can put together for the el Dorado trail!

All that said, while I’ve got the advantage when it comes to covering the town’s culture, it is not easy to find things about the mine that both McLean and Martin missed. They were way more focused on the mining itself and they’re really good at what they do. However, the reason I was talking to Vulcan’s CEO in the first place is because I’ve found production numbers in my archive that are absent, so far as I can tell, in every publication since McLean. And more recently I’ve stumbled upon a powerful new source in the University of Alberta online library – namely The Newfoundland Mining Corporation’s 1881 publication which gives us the exact number of shafts for Little Bay Mine which is something I know McLean didn’t have. So let’s see what we can put together for the el Dorado trail!

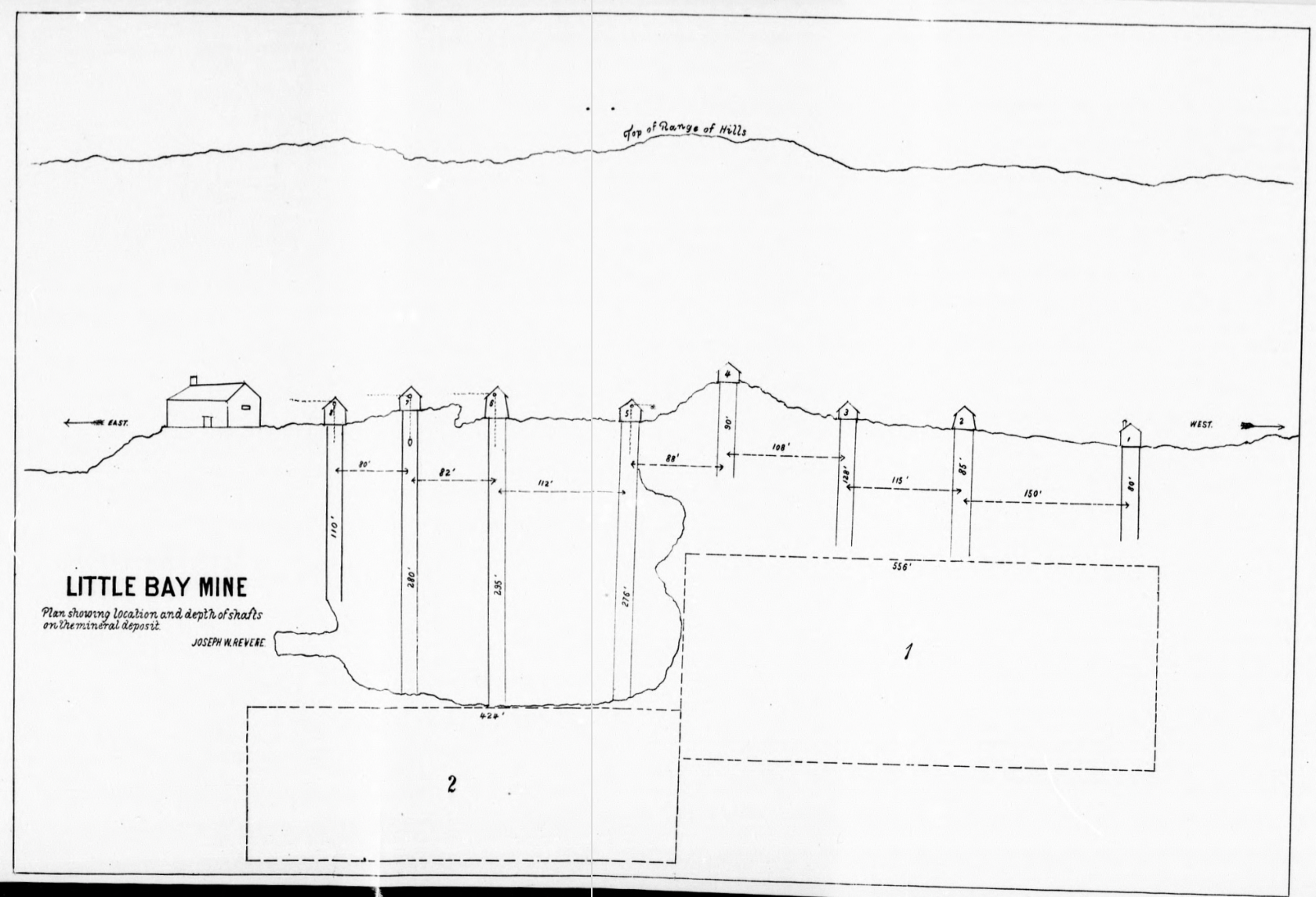

We know from the Company’s 1881 publication that at the time Little Bay mines was sold to Newfoundland Consolidated there were 8 shafts in operation. Those eight shafts were 80 to 120 feet apart and formed a line following the ore body. The deepest shaft sunk for the Little Bay mine was Sirius/Saralis (Seary) Shaft. This is sometimes referred to as the first shaft, however, given it’s description as the deepest I think it more likely to be number 8. According to Martin the first shafts were sunk over November and December of 1878. They were likely sunk down from the original surface workings at Copper Cliff. Rev. Harvey describes Copper Cliff as connected to the Loading Wharf by 3/4 miles of tramway. The Company publication is more exact giving a measurement of 4600 feet. So the placement of Seary can be situated by measuring that distance from the old dock site along the route of the old tramway which can be seen in Parson’s photograph.

From the wording in the Company publication I think it’s a safe bet that all eight shafts were started at roughly the same time before the shipping season closed in December 1878. The stope was 35 feet wide. Hoisting was done by engine with carts drawn by horse. From the Company publication we also get the name of another shaft. Number 2 was called “Frenchman’s” and as we know from Whittier’s writing French was one of the town’s three major languages. It’s a good guess that work was divided linguistically so how it got this name is perhaps obvious. Those are the only two of the original eight I can name but I can fill in some info on other shafts nearby connected to the Little Bay operations.

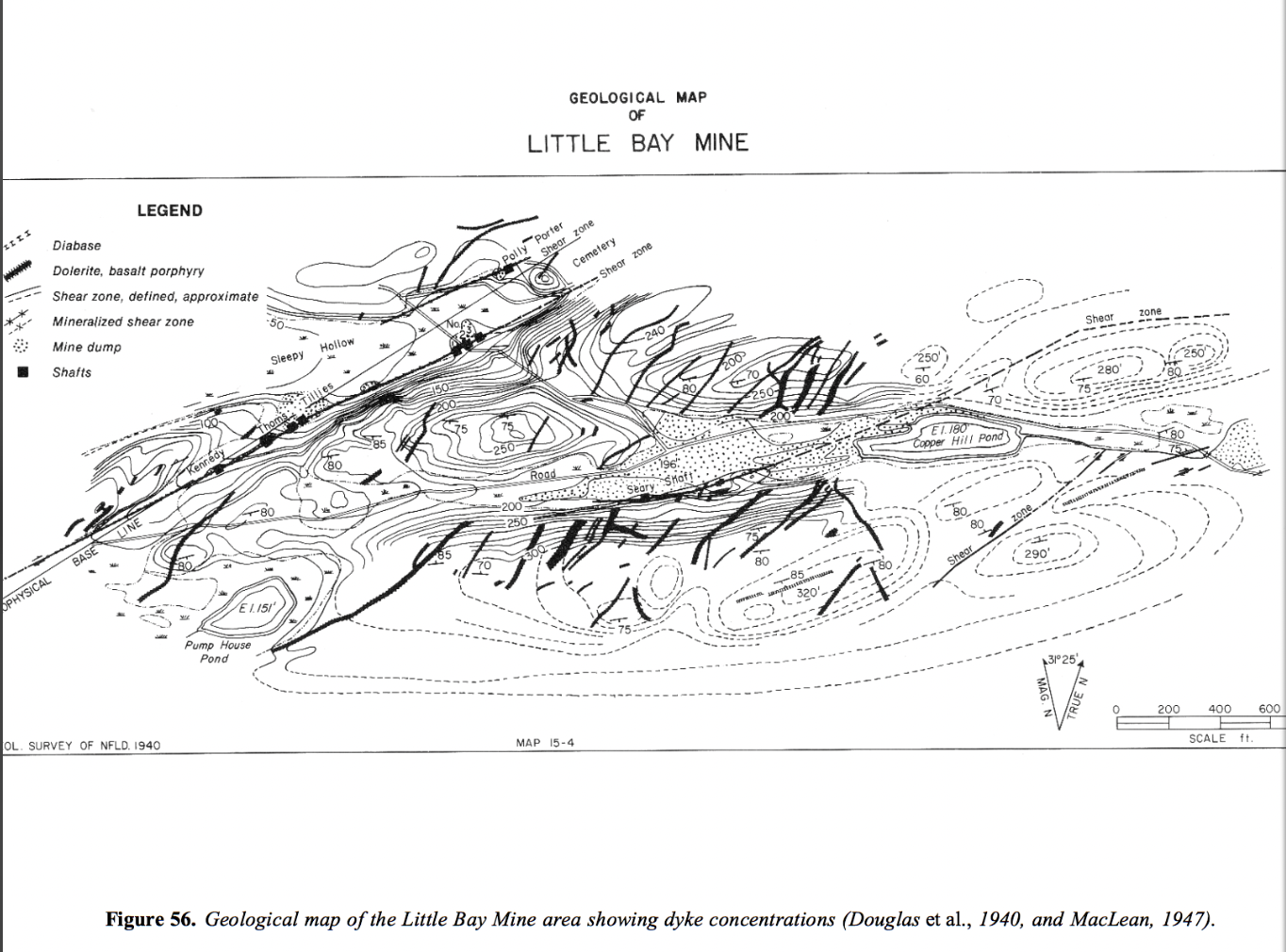

Work was done at Shoal Arm by 1879 after its discovery by Captain Brown from Nova Scotia (Martin / Howley). It was again being worked in 1906 (Howley). Whale’s Back was underway by 1880. The first record I have for it comes from the Twillingate Sun in July that year. This helps us date the Company publication’s information as it states the discovery was only a few months old at the time. This likely means the text info comes from 1880 and not its publication date the following year. Lady Pond was underway at that time as well. It had seven shafts. My first reference to it comes from the Harbour Grace Standard on February 1st 1880. It was reviewed for the period of June 1898 to January 1900 during which time it produced 276 tons (ET March 31 1900). Delaney shaft in St. Patrick’s was worked by Captain Maynard from 1883 (Martin). Government records show it operating again in 1910. Sleepy Hollow had nine shafts. The first was sank in 1898 (Martin). From June 1898 until January 1900 it produced 357 tons of copper ore (ET March 31 1900). It was again drilled in 1906 and 1919 (Douglas, Williams, Rove).

You’ll notice some of those dates fall after 1903/1904. There are a number of stop and go operations after the fires. I know of work done in 1905, 1906, 1916, 1917, 1919, 1921, and 1922. The Western Star reports on production in 1906. That’s the year that the Pilley’s Island Pyrite Company retimbered Seary Shaft while drilling in the area (Kean, Evans, Jenner). We find reports of work being done in 1916 as recorded in the Mail and Advocate and the Western Star with ore being sent to St. John’s at that time.

You’ll notice some of those dates fall after 1903/1904. There are a number of stop and go operations after the fires. I know of work done in 1905, 1906, 1916, 1917, 1919, 1921, and 1922. The Western Star reports on production in 1906. That’s the year that the Pilley’s Island Pyrite Company retimbered Seary Shaft while drilling in the area (Kean, Evans, Jenner). We find reports of work being done in 1916 as recorded in the Mail and Advocate and the Western Star with ore being sent to St. John’s at that time.

You’ll see a number of named shafts on the McLean map. Those are Kennedy, Thoms, and Tillies. Those were sank in 1919 by McKay during his investigation. I’m uncertain if these were reexaminations of existing shafts as there is previous reference to shafts on the Thoms deposit. Polly Porter was discovered in 1917 by miner’s working Sleepy Hollow (ET, March 1917). The Hearn Prospect was discovered in 1932 by Thomas Armstrong and Little Deer was discovered in 1952 by the Falconbridge Nickel Mines Limited (Kean, Evans, Jenner). Both Shellbird and Otter Island have been prospected with Captain Cleary showing an interest in the former. The current claim owner, Kermode, refers to gold on the latter. Lastly, I am having a hell of a time trying to put a date on the Shimmy Pond operation so would welcome any help with that one. If you want to help with research reach out first so I can give you some direction. You can totally find sources I haven’t got but you got a better chance at doing that if you know what I’ve yet to compile in my archive.

And finally, here’s the big reveal: I’ve found that a Mr. Routledge discovered a deposit of copper at Davie’s Pond in the summer of 1887. This is referred to as the Notre Dame Mine. This is backed up by a report from the Engineering and Mining Journal that year which places it 4 miles from Little Bay and 1/4 mile long. So far as I can tell there are no further references to this mine anywhere. I’m pretty sure it got lost after the fires. More recent journals put Davie’s Pond on the same something or another as the Hearn gold prospect so maybe that means there’s gold to be found (again not a geologist!). That said finding a forgotten copper mine has got to be worth something. If you want to strike it rich I’ve probably just given you a means. You just have to find the Notre Dame Mine before Kermode does (they bought the mining rights to the area off of Vulcan last year so I think it’d be theirs). Maybe I should have sold all this data to them but alas I’m committed to a public project. I’ll have to get by on donations. If you’d like to help me out you can find my Patreon here. And if you’d like to help Little Bay’s Heritage Society pay for some of these trail signs (which you totally should) you can reach them by email here – littlebayheritagesociety@gmail.com

PS – If you are from Kermode you can thank me for all this free information by supporting the town’s heritage work. It’d be a good look for a mining operation to do some community building and the whole mining heritage thing is totally thematic.

PPS: If you’ll allow me to show off a bit I’ll demonstrate the value of my approach. Below I’ve filled in some of the production gaps that have been carrying forward since McLean back in ’47. You’re welcome. 😉

Known production numbers:

- 1878: 10,000 tons

- 1880-85: 61,796

- 1885-92: 40,000+

- 1898: 713

- 1899: 647

- 1901: 440

Updated numbers:

- 1879: 19,000 (Deduced from 45,000 total from start in Company publication)

- 1880: 16,000 (TS 80 Nov 18)

- 1881-84: 55,306 (Found by subtracting Company publication number from known)

- 1885: 6490 (ET 86 Jan 20)

1886-92: 33,510 (Found by subtracting previous year’s total from known)

- The total production number from 1878 to 1900 was estimated as 200,000 so feel free to math with that.

Huge thanks go to Justin Gray for putting the new shaft map found below together (it was in two parts when I found it). And as always I appreciate the heck out of Penny Myles for keeping this site up and running as I’m not very techy – hopefully she’ll align the opening image soon! Thanks for reading!