With the rise of digital resources, more and more people are researching their family histories. This has led to a surge of interest in Newfoundland history. Much of this interest comes from people looking to place an ancestor of theirs into their larger historical context. This local attention can give new life to our tourism industry. It is organized online on a handful of websites dedicated to sharing resources and methodologies. I’d like to recognize the efforts of the tireless community organizers behind these fundamentally necessary endeavours for the work they do to maintain and manage the historical research that the province’s tourism success is indebted to. Their work is time consuming, largely voluntary and goes too often unnoticed. It is motivated by love and dedication. Our tourism is fortunate to have impeccable advertising and the success of Newfoundland’s tourism is rightfully celebrated but the resources for the heritage sites and centres it is built upon require community work. I entered into this arena as a novice and have felt welcomed with open arms into a community of amateur historians.

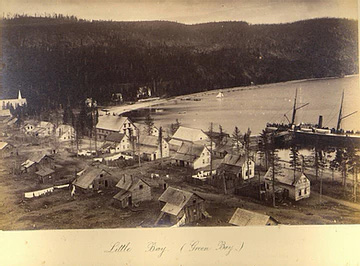

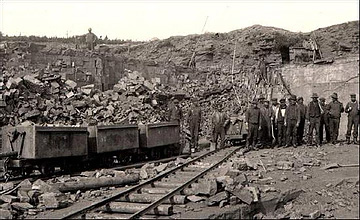

My own efforts on Little Bay focus on one town primarily over a fixed period. Today Little Bay is a small outport but in its heyday from 1878 to 1905 it was one of Newfoundland’s largest centres. For context its peak population was over 2,200 at a time when the population of the island was less than 200,000. I would estimate that between 1 and 1.5% of Newfoundlanders can trace an ancestor to this community which represents less that 0.03% of Newfoundland’s population today. In researching Little Bay I have found a lively historical town. Little Bay was referred to as Newfoundland’s el Dorado, the gem of the island, and even addressed as the beloved Little Bay in St. John’s newspapers. It caught more attention than just the island’s capital and the eyes of the British Empire were on it. I can trace major events in the town through newspapers across the commonwealth and in the United States. While day-to-day events were reported in detail in newspapers across the island. The reason for all this attention was the mining. Mining was a relatively new industry for Newfoundland and Little Bay was vastly outperforming the other smaller operations in the region. In fact, it was one of the best sources of copper in the world and it was expected to overtake fishing as Newfoundland’s main export, giving the island increasing credibility with the British colonies. Newfoundland was stepping onto the world stage largely because of Little Bay and so to the rest of the island the booming mining town was its rising star.

My own efforts on Little Bay focus on one town primarily over a fixed period. Today Little Bay is a small outport but in its heyday from 1878 to 1905 it was one of Newfoundland’s largest centres. For context its peak population was over 2,200 at a time when the population of the island was less than 200,000. I would estimate that between 1 and 1.5% of Newfoundlanders can trace an ancestor to this community which represents less that 0.03% of Newfoundland’s population today. In researching Little Bay I have found a lively historical town. Little Bay was referred to as Newfoundland’s el Dorado, the gem of the island, and even addressed as the beloved Little Bay in St. John’s newspapers. It caught more attention than just the island’s capital and the eyes of the British Empire were on it. I can trace major events in the town through newspapers across the commonwealth and in the United States. While day-to-day events were reported in detail in newspapers across the island. The reason for all this attention was the mining. Mining was a relatively new industry for Newfoundland and Little Bay was vastly outperforming the other smaller operations in the region. In fact, it was one of the best sources of copper in the world and it was expected to overtake fishing as Newfoundland’s main export, giving the island increasing credibility with the British colonies. Newfoundland was stepping onto the world stage largely because of Little Bay and so to the rest of the island the booming mining town was its rising star.

Little Bay endeavoured to make itself as cutting edge as an edge of the world could be. There were plans in place to connect Little Bay to St. John’s by railway. The Little Bay Hotel was one of the best on the island and the town could boast an industrial wharfage that was among the best in the world. The town’s reading room kept publications that covered a vast selection of topics and the magic lantern shows let them see images projected in vivid light. They were interested in engineering and anatomy, motivated less by religion than the generations that followed and inspired by the constant breakthroughs of their new scientific age. The newest steamships would arrive at Little Bay after travelling at speeds previously unheard of: crossing oceans in days that would have recently taken weeks. This is why the town took pride in its telegraph. No more advanced communication technology existed in the 19th century. Telegraph lines provided near instant contact with distant places and made the world a much, much smaller place.

The Premier of Newfoundland, sir William Whiteway served as power of attorney for Baron Franz von Ellershausen, the father of Little Bay. The two men were invested in the mining town together. It was the Baron who suggested an extension of the telegraph line into the northern mining region and it was the Whiteway-Bond Government that saw it done. The telegraph office was one of the first buildings in Little Bay: the Baron saw to that. It was there from the first year of the town in 1878. The telegraph operator assigned to it was a young man, only 19 years of age, his name was Richard Walsh and the Baron likely saw to that as well. As Postmaster, Richard Walsh was responsible not only for telegraph communication but receiving and releasing the town’s mail. His story is his own but from it you can also glimpse the day-to-day operations of telegraph operators more generally. Like the internet is the high-tech communication connecting us across the island today, it’s important to remember how modern the technology of the 19th century would have seemed to the people living with it.

The Premier of Newfoundland, sir William Whiteway served as power of attorney for Baron Franz von Ellershausen, the father of Little Bay. The two men were invested in the mining town together. It was the Baron who suggested an extension of the telegraph line into the northern mining region and it was the Whiteway-Bond Government that saw it done. The telegraph office was one of the first buildings in Little Bay: the Baron saw to that. It was there from the first year of the town in 1878. The telegraph operator assigned to it was a young man, only 19 years of age, his name was Richard Walsh and the Baron likely saw to that as well. As Postmaster, Richard Walsh was responsible not only for telegraph communication but receiving and releasing the town’s mail. His story is his own but from it you can also glimpse the day-to-day operations of telegraph operators more generally. Like the internet is the high-tech communication connecting us across the island today, it’s important to remember how modern the technology of the 19th century would have seemed to the people living with it.

Before arriving in Little Bay in 1878, Richard would have learned morse code, the telegraph operators seem to have been trained under a master / apprentice system so the young Walsh would have first worked under an operator in St. John’s. You can picture the teenager practicing his morse code at the family kitchen table while siblings ran around him. The number of Walshes in the early town leads me to believe that Richard travelled to Little Bay from St. John’s with a sizeable segment of the family. The Walsh family is notoriously difficult to map out genealogically so I can’t say for certain how Richard fits into the other Little Bay Walshes. From the Voter record James Walsh appears to be the senior Walsh in town. James Walsh was a colourful character. He was a shopkeeper in Little Bay and can be found repeatedly in the Supreme Court records, usually for outstanding debts. The politician William Walsh was born in Little Bay at this time which hints at the family’s political pull. I’m imagining a business owning family with political influence that also operates comfortably in darker endeavours. Richard would seem to follow suit. Further, Richard’s sister was married to a famous stage actor in England. She even received a letter from the Queen upon her husband’s death. Postmaster Walsh would have heard from her so there is grounds for the sense of superiority he comes to exhibit.

Before arriving in Little Bay in 1878, Richard would have learned morse code, the telegraph operators seem to have been trained under a master / apprentice system so the young Walsh would have first worked under an operator in St. John’s. You can picture the teenager practicing his morse code at the family kitchen table while siblings ran around him. The number of Walshes in the early town leads me to believe that Richard travelled to Little Bay from St. John’s with a sizeable segment of the family. The Walsh family is notoriously difficult to map out genealogically so I can’t say for certain how Richard fits into the other Little Bay Walshes. From the Voter record James Walsh appears to be the senior Walsh in town. James Walsh was a colourful character. He was a shopkeeper in Little Bay and can be found repeatedly in the Supreme Court records, usually for outstanding debts. The politician William Walsh was born in Little Bay at this time which hints at the family’s political pull. I’m imagining a business owning family with political influence that also operates comfortably in darker endeavours. Richard would seem to follow suit. Further, Richard’s sister was married to a famous stage actor in England. She even received a letter from the Queen upon her husband’s death. Postmaster Walsh would have heard from her so there is grounds for the sense of superiority he comes to exhibit.

I can tell you that Richard David Walsh was born to Edward and Ellen Walsh in St. John’s in 1859. His father worked for H.M. Customs. His father’s government post likely played a large role in landing the teenager the respectable position of Postmaster. Based on the role Baron Ellershausen played in the town’s early appointments, it’s reasonable to assume that the Baron picked Richard Walsh for the prominent position so I’d imagine there is a yet-unknown connection between Edward Walsh and Whiteway. Postmaster Walsh and the Baron in 1880 both aided the building of Little Bay’s RC church “the esteemed telegraph operator, took active part in promoting the good work, and Mr. Ellershausen gave a relay of horses to haul the heavy timber to the plateau on the crest of the hill” (ET July 1903).

Richard Walsh was described in 1886 as “a young man, of prepossessing appearance, with no beard except a slight moustache, he is about the average height, and I should say under thirty. He seems fairly popular but then post-masters never please everybody” (The Colonist Sept 1886). Postmaster Walsh served as executor on several estates. He was a member of the community’s road board, the board of education, and rifle club as well as the secretary for the 1888 fire relief which saw him organizing a concert by the Little Bay Brass Band and soliciting donations from St. John’s in the relief effort. Despite his community efforts, however, he was not well liked and there were countless complaints about both the mail service and its postmaster. Postmaster Walsh was said to be short tempered and discourteous. At the Postoffice the miners learned to “appear as meek and gentle as lambs [or be] in danger of getting [their] heads snapped off” (ET June 1883). It was said “that a man like the Postmaster of Little Bay would not be allowed to hold office in any other of the British possessions” (TS March 1886). He had a temper and was once arrested for beating up the mine’s cashier, Jacob Diem – an assault that took place in the Post Office itself!

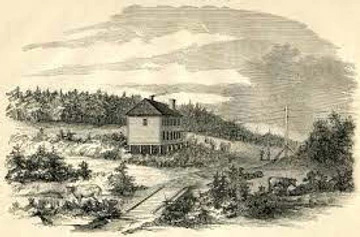

The Post Offices served as the communication hubs of the 19th century. The day-to-day operations of the Postmasters were likely similar across the island. Working from the Post Office they managed the towns’ communication with the outside world. In Little Bay the Post Office could be found sharing a shabby two-story building with the town’s surgery. Inside the post office R.D. Walsh sorted the mail. He also sold postage, some of which depicted images of the town. He may have sold publications too as he worked as an agent for The Carbonear Herald. The Post Office also contained a safe that seems to have functioned like a safety deposit box as indicated in Ernest Lind’s will.

The young man likely found himself in over his head when he started as the Postmaster’s tireless work was rarely satisfactory to the public. A notice posted on the door instructed the public that post office business was transacted out of a small window. Postmaster Walsh would be busy on the days the mail arrived with a crowd composing much of the town and containing all classes of people struggling to push themselves up to the little window for service. The little building was cramped and the people outside would be frustrated. The people wanted the cramped post office replaced with a “more commodious building” (TS, Sept 29, 1888). The town received a new Court House in 1888 and I believe the post office was relocated there.

Postmaster Walsh would have dealt with the captains of the coastal steamers which delivered the mail to Little Bay. The mail route was extremely important to residents as sending telegraphs was expensive. “It is needless to say that this mail [was] of especial interest to the families of miners – the telegraph lines being practically closed against them owing to the high charges for messages” (ET Feb 1884). People kept close tabs on the comings and goings of the mail steamers as evidenced by the journals of both Thomas Wells and Henry Lind. There were favoured steamships and favoured captains and a discrepancy between the number of days mail took to arrive was closely monitored, not just in the town, as the most current and up-to-date information on a steamers location and conditions was quickly telegraphed ahead to keep the island’s other centres informed. Incoming and outgoing telegraphs such as these and other immediate communications would have required Postmaster Walsh to spend his days inside the Post Office and at the ready. Telegraphs were a vital part of the communication system, not just for their own sake but for monitoring mail as well.

Postmaster Walsh would have dealt with the captains of the coastal steamers which delivered the mail to Little Bay. The mail route was extremely important to residents as sending telegraphs was expensive. “It is needless to say that this mail [was] of especial interest to the families of miners – the telegraph lines being practically closed against them owing to the high charges for messages” (ET Feb 1884). People kept close tabs on the comings and goings of the mail steamers as evidenced by the journals of both Thomas Wells and Henry Lind. There were favoured steamships and favoured captains and a discrepancy between the number of days mail took to arrive was closely monitored, not just in the town, as the most current and up-to-date information on a steamers location and conditions was quickly telegraphed ahead to keep the island’s other centres informed. Incoming and outgoing telegraphs such as these and other immediate communications would have required Postmaster Walsh to spend his days inside the Post Office and at the ready. Telegraphs were a vital part of the communication system, not just for their own sake but for monitoring mail as well.

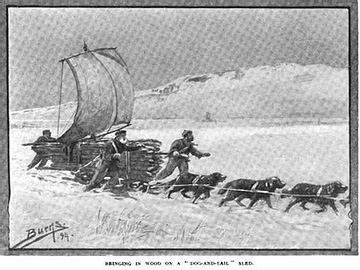

Besides the steamer captains Postmaster Walsh also regularly dealt with the dogsled teams. The mail was moved by dogsled once ice made the steamship deliveries impossible. The mail teams appear to have been hired by government contract. At various points the number of dogsled teams delivering the mail from Little Bay could be as high as four or as low as one. The men who operated them were described as “sturdy, courageous men toughened by the hardships and hazards of the open country in winter. They were dedicated to the task of getting [the] Mail through, come hell or high water; and they were amazingly successful. [. . .] A difficult and responsible job was given to them, and a strong sense of duty to their employer and the people they served inspired and challenged them to preform it with dignity, pride, and efficiency” (NQ V73 No3).

The dogsleds appear to have been equipped with sails allowing wind power to aid their travel. The technology had a downside however as the dog population was ever on the rise. The police journal notes that people could be paid for shooting strays to keep the dog population down. On a more humourous note a story from the journal of Robert Hackett in 1885 mentioned that the dogs from Little Bay returned home to Little Bay if unattended and owing to this him and his men woke up one morning to find themselves deserted and had to walk back. Like the steamers the travel times and conditions of the dogsled teams were also closely monitored. It could be ridiculed or praised as mail from Little Bay could take anywhere from two weeks to two months to reach the capital once the steamers had stopped running. In one letter to the editor this was called a “very imperfect postal connection for so important a part of the colony” (TS February 25, 1888). Another irate complaint over the mail service claimed mail could “be received from China and other distant parts of the Globe within three months [while mail] in the Twillingate post office from Little Bay [could be] over two months old” (TS, May 19, 1888).

The dogsleds appear to have been equipped with sails allowing wind power to aid their travel. The technology had a downside however as the dog population was ever on the rise. The police journal notes that people could be paid for shooting strays to keep the dog population down. On a more humourous note a story from the journal of Robert Hackett in 1885 mentioned that the dogs from Little Bay returned home to Little Bay if unattended and owing to this him and his men woke up one morning to find themselves deserted and had to walk back. Like the steamers the travel times and conditions of the dogsled teams were also closely monitored. It could be ridiculed or praised as mail from Little Bay could take anywhere from two weeks to two months to reach the capital once the steamers had stopped running. In one letter to the editor this was called a “very imperfect postal connection for so important a part of the colony” (TS February 25, 1888). Another irate complaint over the mail service claimed mail could “be received from China and other distant parts of the Globe within three months [while mail] in the Twillingate post office from Little Bay [could be] over two months old” (TS, May 19, 1888).

Many of the problems addressed with Little Bay’s mail were not Walsh’s fault and there was often interest in changing routes to improve communication. Attention was brought to the defective telegraph route as telegraphs from Little Bay to Twillingate went “through various other repeating stations before arriving [and it was] suggested that this route should be abandoned and a line built between [them]” (TS, March 31, 1888). It was also the Government’s intention “to alter the overland winter mail route” (TS, September 22, 1888). This constant need for improvement in communication led E.R. Burgess of Little Bay to attempt domesticating the island’s caribou for mail delivery.

I suspect Walsh dealt with it differently and came to be involved in a media conspiracy with Little Bay’s mine management. The Postmaster created a system of delays for the public that likely eased his work but also appear to have favoured the upper class. Postage stamps would not be sold for four hours before the mail’s departure if the office remained open at all, but it was not unusual for Postmaster Walsh to close the office hours before the mail was sent. This was likely adapted to deal with the surge of people demanding service at the last minute but drew complaint from the populace many of whom wrote letters to the editors of the island’s newspapers. Demands for better mail service were common. The workmen from the mines could not get their mail out of the post office until after the steamer that delivered it had departed. This reportedly went against protocol as the workmen were under the impression that mail should be available just two hours after the boat arrived.

On top of their economic advantage by being able to afford telegraph communication, the upper class would also come to receive their mail first. The workmen were forced to wait through a system of delays both in sending and receiving their mail. I suspect this gap in time allowed the mine management an advantage both in addressing external events to the town and in controlling which information concerning the town got out first. This would have played well with the politics of the island’s newspapers, many of which had corespondents posted in Little Bay but only some of which were politically aligned with the Whiteway government. This would have offered the mine management an added advantage in both dealing with investors as well as the miner’s union. While I lack evidence enough to be certain, concerns raised by one of the journalists assigned to the town leads me to believe that the general public’s impression of Little Bay was influence by the Postmaster’s gatekeeping. Further, the problems with mail delivery while seemingly felt by all classes initially could be bypassed by the mine management who would sometimes send their own curriers when the usual overland mail routes were too slow.

Postmaster Richard Walsh remained in Little Bay after the fires and held the post until sometime between 1909 and 1911 after which he took up the position on Bell Island. He likely knew many people from Little Bay on Bell Island as the Bell Island mine took off after the Little Bay mine had closed. Bell Island would go on to dwarf Little Bay’s mining output and eventually its history with one celebrated and remembered while the other was all but lost to time. Richard Walsh died on Bell Island in 1935. His last years were spent living with two elderly sisters. They likely could not afford to honour him with a gravestone but nevertheless on Bell Island he remains.

Postmaster Richard Walsh remained in Little Bay after the fires and held the post until sometime between 1909 and 1911 after which he took up the position on Bell Island. He likely knew many people from Little Bay on Bell Island as the Bell Island mine took off after the Little Bay mine had closed. Bell Island would go on to dwarf Little Bay’s mining output and eventually its history with one celebrated and remembered while the other was all but lost to time. Richard Walsh died on Bell Island in 1935. His last years were spent living with two elderly sisters. They likely could not afford to honour him with a gravestone but nevertheless on Bell Island he remains.

Postmaster Walsh was a media gatekeeper and played a role in the public’s image of Little Bay. He was overworked, frustrated, and pressured to conform by powerful forces. In the 19th century a place’s public image was presented upon the communication technologies available to its Postmaster. Today, our public image is drafted through social media and advertising. It’s not so dissimilar a process. I hope you’ve enjoyed learning about Postmaster Walsh and the functions of the 19th century communication system. Further, I hope I’ve shown him to be an example of heritage work as well as an example of how media gatekeeping works in public impression.

Newfoundland tourism is built upon storytelling and uncovering this tale took me months of dedicated sleuthing. This work makes me recognize the connection between our local tourism and the endless heritage work done by far better researchers than me. Uncovering and getting to know these long lost Newfoundlaners is a great way to explore the island. Our tourism industry excels at drawing CFAs here but under the pandemic that resource is hurting. This is an opportune time to shift our focus and to support our island by exploring it ourselves. Richard Walsh’s story is Little Bay’s story but it’s also Bell Island’s and it’s also the story of Newfoundland. Newfoundland’s tourism draws upon the work of heritage researchers but our history isn’t just tourism for visitors. We can be tourists of our own heritage. We’re in this bubble together here anyway so it’s the perfect time to get to know the place. Thanks for reading! I hope you enjoy my small contributions to the community’s effort. And to everyone else undertaking this often difficult but endlessly interesting work I thank you!