There was a new Sergeant in town. It was 1883. Sergeant Thomas Wells of the Newfoundland Constabulary arrived in Little Bay on August 3rd. He arrived during the town’s annual regatta but made no mention of it in his journals. He wasn’t there for that. He was a staunch and imposing man with a sense of moral superiority. Little Bay was messy and he was there to clean it up.

There was a new Sergeant in town. It was 1883. Sergeant Thomas Wells of the Newfoundland Constabulary arrived in Little Bay on August 3rd. He arrived during the town’s annual regatta but made no mention of it in his journals. He wasn’t there for that. He was a staunch and imposing man with a sense of moral superiority. Little Bay was messy and he was there to clean it up.

He would have known coming in that the place was dangerous. The suddenly expanding mining town had attracted a rich assortment of colourful characters. Beaten by the cold Atlantic this rugged terrain had been wilderness only five years before and the newly established town was still wild. Criminals operated without concern and there was little police presence. For the week leading up to his arrival the closest officer was in Twillingate. Raids and robberies were ever threatening and drunkards brawled openly in the streets. Crime ran rampant.

Little Bay was overseen by a Magistrate, Magistrate Blandford, and Sergeant Wells’ needed the man’s support. He got it. These two men of authority must have taken an immediate liking to each other as they went right to work. On the first day they put up notices for the Supreme Court, reported a theft, and issued a summons in a case of bastardy. They established a working relationship that people noticed. By the end of that first month the newspapers praised the duo for breaking up the street fights and making many arrests.

The town had an active Temperance movement, the Presbyterian Reverend Fitzpatrick had seen to that. The same man who started the Reading Room that was attached to the Public Hall. Temperance meetings were held in the Public Hall and Sergeant Wells took centre stage at those Temperance meetings. He pushed hard and with intention against all recreational drinking.

The Public Hall also hosted public debates. Little Bay’s public debates were popular events and they could get a little lively. One popular contender was the school teacher E. R. Burgess, Sergeant Wells’ own children’s teacher. Burgess was a local intellectual and the president of the Reading Room. Records of his later life indicate he was fond of the occasional glass himself. Burgess challenged the Sergeant to debate the issue of moderate drinking. It was a showdown that everyone was excited to see. Sergeant Wells’ had openly stated that he believed the moderate drinkers were the worst drinkers for corrupting a town’s moral integrity. Something must have happened before the scheduled debate, however, as Mr. Burgess withdrew his challenge. This was out of character and I suspect some pressure to have been applied off stage.

The town had several establishments licensed to sell alcohol including the Little Bay Hotel and John Lamb’s Skittle Alley. The legal sellers were not above suspicion of also selling it illegally, however, and the police cracked down on them by arresting their clientele. It didn’t take long before they set their sights higher and took aim at the proprietors, first for minor infractions but they didn’t stop there. In December of 1886 they raided the Skittle Alley. Only one month later John Lamb gave testimonial at a Temperance meeting in support of banning the liquor licenses. A month after that the Skittle Alley was torched, likely the work of the town’s suspected arsonist, the tinsmith Robert Malcolm.

The town had several establishments licensed to sell alcohol including the Little Bay Hotel and John Lamb’s Skittle Alley. The legal sellers were not above suspicion of also selling it illegally, however, and the police cracked down on them by arresting their clientele. It didn’t take long before they set their sights higher and took aim at the proprietors, first for minor infractions but they didn’t stop there. In December of 1886 they raided the Skittle Alley. Only one month later John Lamb gave testimonial at a Temperance meeting in support of banning the liquor licenses. A month after that the Skittle Alley was torched, likely the work of the town’s suspected arsonist, the tinsmith Robert Malcolm.

Sergeant Wells had quickly established himself by busting public drunks and cracking down on violence. He shifted the local Temperance debate by taking a very public stand against moderate drinkers, calling them worst than heavy drinkers. He pushed hard for total abstinence. This combination of on-the-ground policing and ideological engagement won many supporters for the Norte Dame Total Abstinence Society. In the end the Sergeant played a major role in shifting support away from the moderate drinkers. He had the support of the church leaders and now with John Lamb turned to his side the legal sales were ended.

The illegal sale of alcohol was another matter. The issue was the sheeban houses, bootlegging and hosting operations ran out of people’s homes. The most notorious of which was the operation of the McLeans. Michael and Mary McLean were a husband and wife team with a seemingly endless set of tricks. They proved themselves difficult antagonists for the Sergeant. It didn’t help that Wells’ own Constables may have been tied up in their operation.

Wells’ high moral standing was not matched by his Constables and their behaviour no doubt contributed to a sense of hypocrisy surrounding their alcohol enforcement. Nothing is ever easy and Constable Meany was particularly problematic. A drinker himself Meany regularly presented conflicts of interest and found trouble in an almost cartoonish fashion; getting tangled up in a robbery, breaking a medical quarantine, and even getting shot by Sergeant Wells’ son. Constable Sutton wasn’t without issue either as he was openly dating the McLean’s daughter. Wells’ wrote to St. John’s requesting new officers but made do with who’d been assigned. The Sergeant did what he could to get the best out of them.

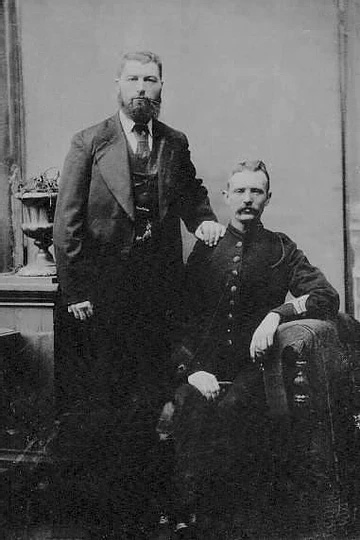

The police engaged in undercover operations around the bay in the fall of 1887. This rouse is what finally netted Little Bay’s most infamous bootleggers. The showdown with the McLean’s required a sting operation. In February the police donned civilian clothes. Using putty, Wells applied a fake nose. He shaved off his beard and dyed his hair black. They took a boat to the residence of Michael and Mary McLean and pretended to be visiting from out of town. Their costumes worked. During the bust Mary McLean caught the Sergeant by the collar yelling “I am damned if you will git the jar Wells, I’ll die first” and she cursed him further at court saying “Oh Wells, you are a hard man!—‘the foxes have holes, and birds of the air nests,’ but you hath not a friend anywhere. Wells your name is a terror to me.’ Long may it continue a terror to the evil doer!” This task earned him and his police force a rather cool nickname – The Invincibles!

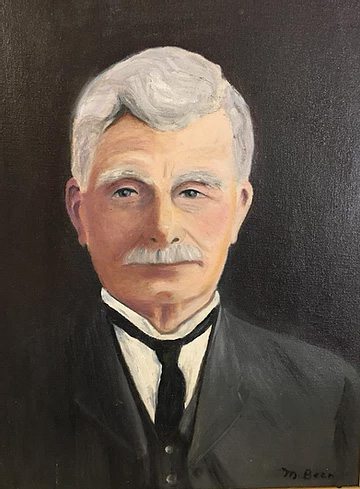

The Temperance Movement in Little Bay was largely successful with the local bars closing up shop in 1887. During Sergeant Thomas Wells’ time in office the town saw robberies, jail breaks, and no shortage of violence but under his mindful watch many were caught and answered for their crimes. His little gaol was rarely empty. He’d eventually retired from policing but stayed in Little Bay to become the town’s second Magistrate. In a way he still watches over the place as his portrait (seen at the beginning of this article) still hangs on the wall in Little Bay’s town office.

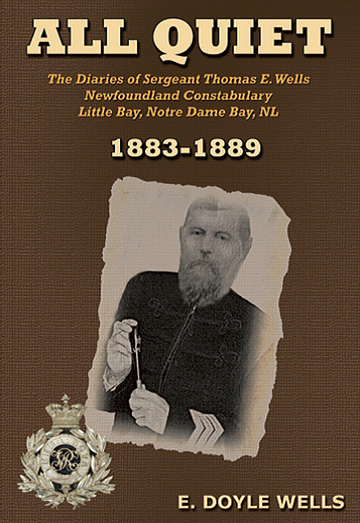

If you’d like to experience the day-to-day life of the town from Sergeant Wells’ perspective you’re in luck. I owe much thanks to Doyle Wells for publishing his great grandfather’s police journals. If you haven’t already go and buy a copy of his book. I did my best not to overlap him in this piece by focusing on my other sources but it was influential in getting me started on this project – it also makes for a fascinating read!

If you’d like to experience the day-to-day life of the town from Sergeant Wells’ perspective you’re in luck. I owe much thanks to Doyle Wells for publishing his great grandfather’s police journals. If you haven’t already go and buy a copy of his book. I did my best not to overlap him in this piece by focusing on my other sources but it was influential in getting me started on this project – it also makes for a fascinating read!

I’d like to thank Doyle Wells for all he has done to support this project and further thanks to all of you for following along. I hope you liked this piece. If you want to support my work there’s a Patreon page and if money is too much to ask you can always share my posts from the Facebook page. As always – thanks for reading!