Little Bay suffered four major fires. I’ve covered the fires of 1888, 1903, and 1904. What follows is what I’ve been able to discern about the blaze of ’81.

Press Release

This is the story of how, in the summer of 1881, everyone thought Little Bay burned down.

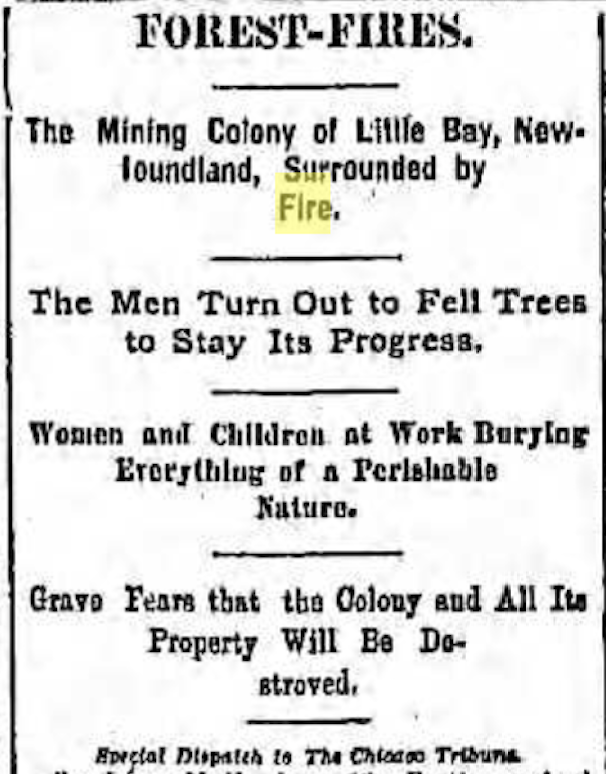

In cities across North America people opened their papers on the morning of June 17th to some pretty scary news from Newfoundland. A press release had gone out from the New York Herald that day with a story. The promising mining settlement in Newfoundland was surrounded by a forest fire. The town of 2000 was filling with smoke and mere moments away from its end.

Faced with imminent destruction the mining captain had dispatched 200 miners to fell the trees out from the mining quarter. The rest, composed of 600 miners and their wives and children, were busy burying the town’s furniture and utensils. Two large iron steamers had been detained for evacuation. Six houses were already lost and the town was filling with smoke. The fire was at all sides of the town and the people rushed against it with air thick and unbreathable. When the steamship Hercules departed the town the prospects of survival were gloomy but bands of axemen were building fire-breaks as quickly as possible. With telegraph lines down the world waited with baited breath for any news of Little Bay. Hopes were hung on a promise of rain.

At least this was how the fire was reported internationally. Some local papers contradicted this description. Sorting out the fact from the fiction with this one proved an undertaking.

Origins

The origins of the ’81 blaze remain a mystery but several rumours were put forward in local papers. One claimed a spark fell from a tilt’s stovepipe, another said a man was burning stumps and lost control, yet another put the blame on John Wilson’s Lady Pond mine, and finally suspicion fell to an agricultural clearing effort near Indian Brook. An investigation was later performed by Magistrate Blandford but if culprits were named I’ve yet to find them. Taken together the rumours and context suggest an area of origin for the blaze. I feel comfortable saying it started somewhere between Little Bay and modern day Springdale. I’d place it closer to the latter. The earliest encounter I’ve found recorded takes place on June 10th 1881 in the vicinity of Green Island

Green Island

Green Island was the site of Mr. Curtis’ sawmill. Located just a few hundred yards from the mainland (again, modern day Springdale), it was the site of several mill houses. There was a wharf on the side facing the mainland. On this day it was occupied by Little Bay Mine’s steam-tug, the ‘Hiram Perry Jr.’ which had nine or ten men onboard. I put them under the command of Captain Dean. There were six men on Green Island itself that morning as Mr. Curtis had left with the rest of his lumberers on Andrew Roberts’ schooner the ‘Young Builder’. They were now five miles up the bay.

We find our only first-hand account submitted to the editor of the Twillingate Sun on July 14th. It gives the particulars from a perspective on Green Island where smoke was first spotted at noon. It was rising from about a half a mile away on the mainland. Three men took a boat across to investigate. They found a forest fire well beyond their ability and so hightailed it back to the island. It was quickly realized that due to the south-west wind the fire would strike an occupied house on the mainland. Four men left the island to collect the women and children there.

The wind turned westerly by 3 o’clock and was blowing strong. It pushed the blaze in the direction of Green Island and brought more homes on the mainland into the path of the blaze. They were enveloped in smoke suddenly and so abandoned their belongings in a rush to cross the water. Behind them the fire consumed their property. It took only thirty minutes to burn everything they owned. Their boats were not as fast as the embers and Green Island was ablaze before they landed – out of the frying pan and quite literally into the fire.

The Hiram Perry refused requests to intervene and instead steamed around to the other side of the island. Two men were still present on Green Island and quickly escorted the refugees to the waiting steamship on the opposite side. The Hiram Perry took everyone onboard. The tug steamed up the bay to find Mr. Curtis and inform him of the ongoing destruction of his operation. Captain Roberts sailed everyone back. With the extra hands the fire was brought under control in short order. A lot was lost, including Curtis’ new home but the sawmill was saved providing survivors with their lumbering livelihoods and giving rebuilding efforts a means to process wood. The company store was also saved, a fact credited to providence as it was so near the blaze. In the days that followed it provided their only shelter. They huddled together during those difficult days.

I don’t have a source for what the Hiram Perry did next but I think it’s a safe bet that the mining company’s steamer would continue northward bringing warning to her home port. Little Bay braced for the incoming inferno.

Hall’s Bay

Others were not so informed. The next day, on the 11th the fire hit the Hall’s Bay mining camp (later renamed Stirling Mine) without warning. They were entirely unprepared. Once again, the company store was saved as well as the mine captain’s cottage due to tremendous efforts by the men. Of the men themselves, composed of twenty miners, they lost everything they’d brought to the work camp along with the five houses they shared between them. They were left destitute but they were all still alive. This was 15 miles west of Little Bay.

The blaze swept outward making its way to Robert’s Arm where another mining camp was located. This was a larger operation with roughly one hundred miners employed. They were successful in their efforts against the fire there and saved the site. The fire also reached South-West Arm. I suspect this refers to the south-west arm of Green Bay where another small mining camp was being run by Mr. White. What became of this site remains unknown.

Little Bay

The fire made its way to Little Bay but untangling reports of how it played out there has been challenging. Most of my information comes from newspapers. This presents a number of problems. The main issue is conflicting reporting. I’ve managed to identify three distinct lines of narrative. The first follows the international press release, the second spawns out of early local rumours, and the last discredits the first. I’ve compared each of these lineages and weighed them against a first-hand account of the aftermath recorded by Captain Kennedy. I’ll give you the scene again as per the press release with a few details from local papers added. Afterward I’ll point out where doubt can be cast.

The first issue is placing an exact date on the fire in Little Bay. I know that Little Bay was in danger for “two or three days” and the listed ordering of events suggests it occurred chronologically after the burning of the Hall’s Bay camp on the 11th. Reporting on Little Bay was sourced to the Hercules after its arrival in St. John’s on the 16th. The steamer had left Little Bay at the hight of the threat. I put its departure on the 14th. Taken together I’m inclined to think that the fire arrived at Little Bay on the 13th and surrounded the town over the next two days. The inferno was finally defeated by rain on the 16th. These dates may be adjusted if new sources are uncovered.

One of the things we can know is that the town had knowledge of the incoming fire which gave them time to prepare. The town’s telegraphic communication was likely cut-off by the fire. This is indicated in the international press release but also accounts for the confused reporting itself. I think it likely that the Hiram Perry Jr. had arrived in time to warn them. The town, further, seems to have had knowledge of the events at Green Island and the Hall’s Bay mining camp which could be explained by this. If I’m right Little Bay owes its response to the efforts of Captain Dean but I can’t prove that. It’d be nice to give him proper credit.

I can tell you what Little Bay’s preparations looked like. Little Bay mine employed 800 men and supported a town composed mostly of their families. As we have seen in other instances, most notably with the original construction of the town, the power of the mine manager to organize labour in the company town was quite impressive. Manager Guzman could make use of the entire population of 2000 and in this instance he did just that. Here we get a glimpse of what that looked like.

The 800 miners were split into two primary tasks. 200 men were under the charge of the mining captain who, although unnamed, I’m guessing to be Phillip McVicar. These men were assigned to felling trees and began cutting back the surrounding forest with axes. The axe-men were responsible for making the fire-breaks. The other 600 men along with the women and children set to work digging trenches and burying the town’s valuables. Those are the two fire duties I’m aware of but I think it’s a safe bet that they would have been soaking everything in water as we’ve seen this practice elsewhere.

This work was done with the entire town encased in flames. The fire came at the town from all sides and with miles of burning timbre behind it. The townsfolk worked within a cloud of smoke steadily for at least two days. During this there were two large international steamers which had been loading ore at the Loading Wharf. They were detained as a backup in case escape proved necessary.

Media Analysis

According to an article in the Terra Nova Advocate on June 24th there were two or three square miles of woods in Little Bay which were not felled due to it belonging to Guzman. It claimed that five houses had burned including the Manager’s cottage and possibly the Magistrate’s home (I’m inclined to place this in the area above Lind’s Pond). The international press release, which went out on June 17th claimed the loss of six houses. The Evening Telegram later took issue with that version and accused the New York Herald of sensationalizing the event. It counter-claimed that only three shanties were lost. The only paper I’ve found to retract the press release after this was the Lancaster Daily.

The press release was certainly sensational. However, I’m not inclined to agree with the Evening Telegram’s reassessment of it. There are a couple of reasons for this. Foremost is that the Telegram shoo-shoos the claim that the miner’s were burying their valuables. I’m quite certain this occurred. Aside from it being a general practice that we see take place with other fires at Little Bay, it is also recorded here by Captain Kennedy who was present in the immediate aftermath. Next is the criticism of people taking shelter on the steamers. As far as I can discern this was never said. What was said was that two steamers were detained as a precaution. There were two present when Kennedy arrived. There were often two present and the idea that Manager Guzman stalled them as a precaution seems entirely reasonable. So, with that in mind, the claim that only three shanties were lost feels disingenuous. Even the choice of the word ‘shanties’ is suspicious. That said, if property as noteworthy as the Manager’s cottage and the Magistrate’s home were lost it is odd that, that isn’t mentioned elsewhere. The truth is probably in the middle with a half dozen miner’s homes lost. Kennedy mentions that the mine’s magazine was dangerously close to combustion which certainly corresponds the proximity of the threat. I should note that the story about Guzman’s cottage comes from the Terra Nova Advocate and drew openly from rumours on the ground.

Now, I’ll attempt to outline how I think this media fiasco played out. The first reports of the fire didn’t hit the local press until June 16th. With the telegraph line down Little Bay’s communication was cut-off. The media (both local and international) got their stories from the Hercules. That vessel left Little Bay at the height of the threat and had a couple of days before arriving at St. John’s. The idea that Little Bay was at risk of imminent destruction was what was said because that was precisely what was witnessed. Everyone first got the news from the Hercules and the panic of the Hercules’ passengers accounts for why it was so dire. The news came already embellished. I think this gives weight to the press release’s narrative, sensational as it was.

There is something else to consider as well. The Chicago Tribune had received a special dispatch from St. John’s on the 17th. Its story was lengthy and detailed. The town was described with a population of 2000 people composed of roughly 800 miners and their families. Its copper wealth was reported to be enormous with 40,000 tons of ore shipped seasonally. It had information on Little Bay’s demographics as well as the mine’s production. This information appears accurate and lines up with data recorded by Captain Kennedy the following week. It also lines up well with reports on the mine we find in other media about this time. I’m inclined to think that the Tribune already had a story in the works and the fire got tagged on to an existing draft.

The reaction of the Evening Telegram is interesting. It appears more interested in discrediting the New York Herald then getting the facts straighten out. I’ll point out that this fire happened during the planned sale of the Little Bay mine. That could explain both the Tribune’s details and the Telegram’s dismissive reaction. The first was originally a sales pitch and the second was invested in the sale. The Telegram doesn’t just downplay the fire’s damages, it also points out that the fire had improved mineral access in the region by removing forest. This highlighted an increased value of the property at a time when making the mine look valuable was valuable itself. A few leaps of logic later and maybe we could account for covering up the loss of Guzman’s cottage if it actually transpired. This all happened just before a British company bought Little Bay Mine – don’t cry in front of the Englishmen!

Aftermath

I’ll contrast the Telegram’s dismissal of the damages with what we know of the aftermath. Besides the losses suffered at Green Island and the Hall’s Bay mining camp it seems likely that the Lady Pond operation and an Indian Brook community were also impacted. It would be hard to blame someone for starting a fire if they didn’t experience it. This helps us get an idea of the fire’s range. From Kennedy we know that there was massive destruction of the woodland across much of the north side of Notre Dame Bay. The fire impacted South West Arm (I believe this refers to the mining operation in Green Bay), Hall’s Bay, Little Bay, Green Island, Indian Brook, and Robert’s Arm. The last is the most surprising as the fire would have to have jumped the water or burned around the other side of the bay. A few shanties indeed!

I’ll close by following the advice of Mr. Rogers. After a crisis we should look for the helpers. On June 18th the HMS Druid arrived at Hall’s Bay. This was fortunate happenstance. They found the survivors of the Green Island sawmill operation sheltering together in the company store. The unexpected arrival of the British Navy was well timed. Captain Kennedy offered what assistance he could; taking people onboard for food and tasking a dozen carpenters with rebuilding. Mine Manager Guzman also sent men to help out. The pair were thanked for their efforts along with Captain Andrew Roberts of Twillingate for kindly offered and much appreciated help.

I’m sorry I couldn’t bring you a clearer story this time. There’s still much unknown. I’ll update if I get more information. This one was super hard. My sources were few and contradictory. I did my best. I hope it was ok!

Thanks for reading!

Sources:

- Carbonear Herald, July 1 1881

- Chicago Tribune, June 17 1881

- Evening Telegram, June 16, June 22, July 21 1881

- Harbour Grace Standard, July 2, July 6, July 9, July 16 1881

- Kennedy, Sporting Notes

- New York Herald press release (Belleville Telescope, Boston Post, Daily True American, Iola Register, Lancaster Daily, Omaha Daily, Philadelphia Inquirer, Toronto Daily), June 17 1881

- Twillingate Sun, June 16, July 7, July 14 1881