If you’ve been following my work you’ll know I’ve been trying to separate two fires which impacted Little Bay in 1903 and 1904. I posted a piece with my findings on the 1903 fire. In this piece I’ll attempt to sort out the references to the 1904 fire. I don’t know if anyone else is as concerned about properly sorting out these two events as I am but in case anyone follows after my work they’ll see how I came to my conclusions. Unfortunately, I lack the first hand accounts of this blaze that I had for the other one so I’ll have to rely heavily on the newspapers and the Twillingate Sun for this period appears to be missing. I’ve done my best to fact check where possible.

If you’ve been following my work you’ll know I’ve been trying to separate two fires which impacted Little Bay in 1903 and 1904. I posted a piece with my findings on the 1903 fire. In this piece I’ll attempt to sort out the references to the 1904 fire. I don’t know if anyone else is as concerned about properly sorting out these two events as I am but in case anyone follows after my work they’ll see how I came to my conclusions. Unfortunately, I lack the first hand accounts of this blaze that I had for the other one so I’ll have to rely heavily on the newspapers and the Twillingate Sun for this period appears to be missing. I’ve done my best to fact check where possible.

If you do a search online for the fire that destroyed Little Bay you’ll likely find references to a 1904 forest fire which burned out an awful lot of Notre Dame Bay that summer. If you go a little further and checkout some books from your local library you’ll find a few which mention Little Bay’s fire. They’ll mostly place it in 1904, mostly. Occasionally it’ll drift into 1905 and I once found it placed in 1907 but mostly it’ll be put in 1904. You’ll find a line which goes like this – “the 1904 fire devastated Little Bay, left 300 people homeless, and destroyed early records” or something along those lines. If you go deeper down this rabbit hole by searching old newspapers you’ll come across a press release which goes “forest fires have destroyed the hamlet of Little Bay and 300 families are homeless. Two men have drowned. The steamer Prospero has embarked the women and children. The men are fighting the flames in an effort to prevent the fires from covering a wider area. The government is providing food and shelter to the destitute” and it is from that press release that following authors took their cue. That press release went really wide. I’ve found it in dozens of newspapers across various countries and if you really dig you’ll find it written in more languages than just English. The problem is it got the facts wrong.

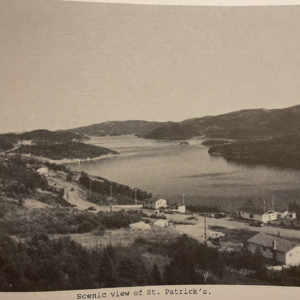

I’ll attempt to set the record straight here. The forest fire started on August 27th, 1904. It spread far as there was a terrible wind storm raging. In communities as far apart as Pilley’s Island and Glenwood people would end up running with buckets of water to protect their towns from the potentially incoming flames. It was the next day on Sunday, the 28th, that it struck St. Patrick’s. We can deduce that the wind was blowing northward as it appears to have hit Springdale first. The townsfolk had time to prepare for its arrival, likely because of the telegraph line. There were mostly women and children present as due to the lack of mining work most of the men were “absent to the fishery and elsewhere” (ET, Oct 11, 1904). Folk wetted everything they could and buried their valuables underground as was the practice.

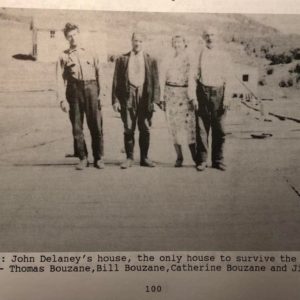

All preparations ended when the wall of flames arrived. Most people ran for their lives. The families of Charles and Philip Baker were said to have lost the most as the money their wives had buried had been lost as well as their homes, belongings, and animals. The elderly Captain John Delaney was not about to let a little thing like a forest fire destroy his home and fought hardest to protect it. His efforts were rewarded but the other 40 homes there were burned down to ashes. The S.S. Prospero was dispatched to Little Bay from Tilt Cove. It returned on the 29th carrying the 40 families that had lost their homes to the blaze. That steamer next returned to Little Bay towing fishing boats behind it to provide room for household valuables still threatened by the fire (Free Press, Sept, 1904).

As I’ve explored elsewhere St. Patrick’s at this time was largely considered an extension of Little Bay and would be written as “St. Patrick’s, Little Bay” in media if specified. Often it was just called Little Bay. That likely contributed to what happened next. The following day, on August 30th, Inspector General McCowen received the following message in St. John’s – “Forest fires are raging all over North Side of Notre Dame Bay. Little Bay is swept. Three hundred homeless. All are on board Prospero, which is detained to shelter them” (ET, Aug 30, 1904). It was this statement which formed the basis of the international press report. This is also the point at which we start seeing local coverage that Little Bay had been completely destroyed. By this time the telegraph lines were lost to the fire so information on the blaze was slowed down. News outlets waited on mail coming by steamship. Meanwhile the existing misinformed reports went out internationally.

On September 1st Superintendent Sullivan arrived at St. John’s from Notre Dame Bay and reported to the Government on the fire which was still ongoing. The whole north side of Green Bay was on fire by this time. It was not until September 6th that the Evening Telegram received updated information by mail which said “Little Bay is all right so far, but up the bay at St. Patrick’s and Springdale there has been much destruction” (ET, Sept 6, 1904).

That was the same day that tensions started to release in Little Bay as rain finally fell there. By now people in Newfoundland had somewhat of an idea about which part of Little Bay was lost – it was St. Patrick’s not The Bight. However, the Western Star in Corner Brook still reported on the 7th that there were “upwards of 300 persons rendered homeless” as had been reported earlier (WS, Sept 7, 1904).

It was not until the smoke had cleared on September 8th that proper information on the damages finally made its way to print. It was reported that Springdale had lost 14 homes while in St. Patrick’s over 40 families were homeless with much of the town’s crops and animals gone as well (ET, Sept 8, 1904). Most of the people burnt out lost everything they possessed (ET, Sept 6, 1904).

There was a lot of thanks and appreciation given to the government’s response to this event. In particular to MHA George Roberts for the aid given to St. Patrick’s, Little Bay. Donations were taken up in various parts of the Island for relief (WS, Sept 7, 1904). On October 12th politicians Bond and Clift visited Little Bay where “they were met at the wharf and given a grand reception. Fire works and guns along the route to the court house, where a large and enthusiastic meeting was held” (ET, Oct 17, 1904).

Boyles writes that less than two weeks after the fire Springdale saw 13 houses under construction. I suspect the same is true of St. Patrick’s. The exception was Captain Delaney’s home which was the only one still standing there. It became part of the local folklore as a result. It was printed that he was due great credit for his “heroic and almost superhuman efforts to save property. It must have been very hard on a man of his age to stand fire and smoke such as was witnessed that day in St. Patrick’s (ET, Oct 11, 1904).

Boyles writes that less than two weeks after the fire Springdale saw 13 houses under construction. I suspect the same is true of St. Patrick’s. The exception was Captain Delaney’s home which was the only one still standing there. It became part of the local folklore as a result. It was printed that he was due great credit for his “heroic and almost superhuman efforts to save property. It must have been very hard on a man of his age to stand fire and smoke such as was witnessed that day in St. Patrick’s (ET, Oct 11, 1904).

By all accounts The Bight part of Little Bay survived this fire intact but you’ll have a time trying to find it recorded as such. The reasons for this are varied. As I explored in my piece on the 1903 fire the two fires got merged into one event; they were close together in time, the population was rapidly decreasing, and the 1904 fire dominated both memory and history. I hope I’ve successfully further demonstrated in this piece how the written record was informed by early and far reaching misreported details.

In considering the book references together you’ll see a pattern. Martin’s ‘Once Upon a Mine’ has Little Bay wiped out by a 1904 fire without one in 1903. The same is true for local histories like ‘Moments in Time’ and Boyles ‘History of the United Church, Springdale’ but not everyone missed it. I stand corrected on my claim that no one had the 1903 fire at all. ‘The History of the Masonic Lodge’ records that “on May 18th, 1903, a great fire swept over Little Bay destroying 34 dwelling homes [and] a forest fire, raged across Little Bay on the 27th of August the following year leaving 300 persons homeless” but as I’ve shown that 300 persons was reported as 300 houses but was actually 40. You’ll note that this still has the claim that Little Bay was burned in 1904. It really wasn’t. At least not Little Bay as it is known today. What burned was St. Patrick’s. You can see now how far reaching that press release actually was. We’re still quoting from it albeit indirectly. As for the two men supposedly drowned escaping the flames – I still can’t find them.

There can be said to be one death from this fire, however. While St. Patrick’s was burning the people in The Bight were being sheltered. Their Magistrate, Mr. J.B. Blandford rushed from site to site tending to his charge. During this he fell and broke his leg. It never fully healed and in his obituary four years later in 1908 it was said to be the cause of his death.

The possible causes of the 1904 fire were pondered broadly. Some people blamed lighting, while some others blamed the railway, and others still thought the blame rested on “irresponsible individuals—tourists, sportsmen, and berry-pickers—who are very apt to light fires anywhere” (ET, Sept 8, 1904). I don’t think its unrelated that Newfoundland passed The Forest Fire Act the following year in 1905. So some good came out of this terrible event.

I’ll close with a request of my fellow researchers. According to the Evening Telegram Little Bay’s photographer L. Windsor left town after the fire on October 12th. I know nothing else about this man yet his photography of the town might still exist. I’d welcome any help identifying this fellow so that, if we’re really lucky, it leads to his surviving photographs of Little Bay.

That’s it folks – thanks for reading!