Little Bay mines had organized labour. There had been a strike in April of 1883 (Martin) and the potential of one was again noted in March of 1884 (Wells). As I’ve discussed elsewhere I believe it was this organized labour movement which contributed to the corrupt Mine Manager Wallace being chased out of town. He was replaced by Mine Manager Whyte and it was Whyte’s more benevolent use of the Company Town model and his collaboration with Mr. E.R. Burgess that saw that former Church of England schoolteacher’s political rise.

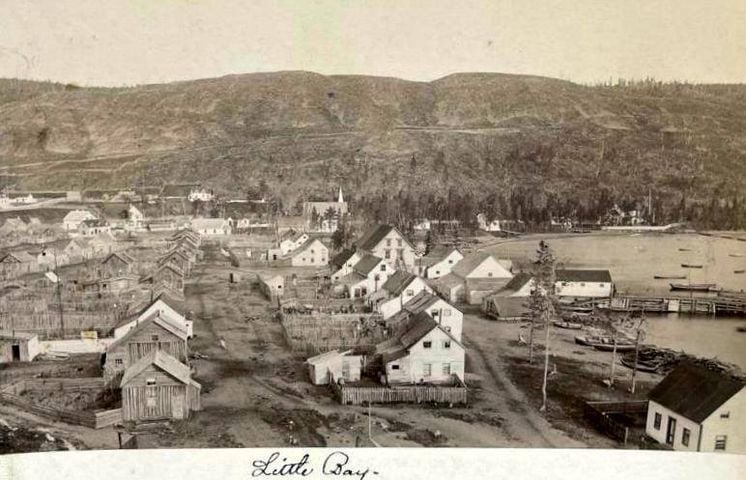

1888 and 1889 found things going well in Little Bay. The mine was booming and the community was seeing both growth and investment. Nevertheless, the working men remained vigilant for despite a more equitable arrangement there was still a great discrepancy in power and the miners had history with the mine and the government. They remembered conspiracies and they kept watchful eyes. The previous abuse of mining grants and the agriculture act had left a bad taste. It was into this context that an announcement printed in the Royal Gazette would stir up old animosities. The resulting political landscape might just offer us a potential candidate for a man responsible for organizing local labour.

William Charles Lacey was born in St. John’s in 1843 to Philip and Mary Lacey. He married Lavinia Manley in Boston in 1872. He is found back in Newfoundland with the birth of his son James in Betts Cove in 1876 suggesting an employment history in mining prior to his arrival in Little Bay sometime after 1878. We first find him recorded in Little Bay on September 3rd 1889 when he is called to speak for the working men at a Public Hall meeting as described in what follows (sourced from articles in the Evening Telegram and St. John’s Colonist that October).

The Public Hall was filled to capacity that evening. The miners present numbered in the hundreds. The crowd was unruly. James Walsh attempted to call the meeting to order. He appealed to those gathered there to nominate a chairman but one after another those nominated each refused the chair. That was until the name William Lacey was suggested. He answered the call and stood for the men.

William Lacey was described possessing “manly dignity, courtesy, and ability” and he rose before an assembly that cheered for him. His next moves make me question just how organic this whole event really was. It feels planned. He waits for the accolades to subside before speaking and he doesn’t speak as the meeting’s chairman first, instead like someone sensing a trap, he points out that the meeting would not be legal unless someone was appointed as secretary. So once again names are suggested from the crowd and once again, one after another, the responsibility is rejected. I’ll note here that this isn’t the usual way Little Bay’s Public Hall meetings went down at all. There’s something at play here and Lacey seems to know it. I’ll also note that James Walsh is elsewhere described as William Lacey’s right-hand-man further suggesting that what is happening in this scene was plotted.

Next, James Walsh hands Lacey a written apology from Mr. Burgess for his absence but Mr. Lacey refuses to even look at it. Instead he took to dressing down those present who had been asked and refused to take any responsibility for the meeting. He zeros in on shopkeeper Reddin, chemist Thompson, schoolteacher Coady, and paymaster Lind.

Finally he addresses the crowd.

“Gentlemen, I accept the chairmanship of this vast assemblage, as a great honour to so humble an individual as myself, to be selected to preside over a meeting constituting so much intelligence and independence as I see here before me tonight. I thank you most sincerely for the honour you have conferred upon me, but I regret that your superior judgement did not council you to select some other gentleman person more worthy of your choice. We are assembled here this evening, gentlemen, not, as many of you may suppose, to exchange our views and opinions as to the political chances of Premier Thorburn or his more fortunate opponent, Sir William Whiteway, in the pending election contest, but we are here tonight, and I hope unanimously so, to protest against one of the greatest, if not the greatest, injurious monopolies that has ever been legitimately attempted upon the unfortunate labouring class of Newfoundland”

He goes on to outline the announcement that timber rights in the area would be granted to four men; Harvey, Monroe, Bishop, and Henderson. This is seen as monopolizing a resource the men require and an obvious ploy to draw money from working men into the hands of the rich as supported by the government. It’s part of a pattern of behaviour witnessed previously with the region’s mining and agricultural grants. Keep in mind that this is coming at the heels of the 1888 fire.

On October 2nd Lacey submitted a petition from the inhabitants of Little Bay in opposition to those large scale timber grants which had amassed 400 signatures. He had identified his political enemies and this battle would not be the end of his war.

On October 24th there was another meeting held in the Public Hall. This one concerned the upcoming political election and centred around the local standard bearers of the Whiteway campaign, namely; Thompson, Peyton, and Burgess. Captain Stewart was chairman. Mr. Lacey once again rose to speak. Unfortunately, his words on this night were not recorded (ET, 1889, Oct 29).

The vote was held on November 6th. That same day Mr. Knight, in St. John’s, received a telegram from Little Bay. It was sent by a Mr. March and in it Mr. Burgess, the local Whiteway candidate, was accused of solicitation in a bid intended to undermine him in the polls that day (TS, 1889, Nov 9). It doesn’t work and Burgess is elected.

On March 13th William Lacey pens a letter to the Saint Johns Evening Herald in which he airs his grievances against the newly elected Mr. Burgess as well as Mine Captain Stewart. Claiming that they are not acting in the interest of the working men; he accuses Burgess of being two-faced and obtaining miner’s signatures under threat of reprisal from mine management and he accuses Stewart of setting up cheap labour for construction of the railway (SJEH, 1890, April 14).

On the 16th of June tragedy strikes and William Lacey’s wife Lavinia dies in childbirth leaving him to raise their five children alone (HGS, 1890, July 4). This is also the month in which he takes on the duties of handling the freight received from coastal boats (SJEH, 1891, Oct 28).

On March 24th 1891 Little Bay witnessed the largest meeting ever assembled at the Public Hall. It concerned the French Shore treaty. Mr. Lacey is listed only after Father O’Flynn in its list of speakers demonstrating his recognized and continuing political involvement (ET, 1891, March 25). Around this time Mr. Lacey sued Mr. Burgess for reasons yet unknown but we do know that the related ruling by Magistrate Blandford was not to Mr. Lacey’s satisfaction (SJEH, 1891, Oct 28).

Over the course of these events the people of Little Bay had been pressing the government for a new public wharf. This was finally granted them in April of 1891 and credited to the efforts of Mr. Burgess for his work organizing signatures for a petition the previous year (SJC, 1891, April 15). Mr. Lacey started collecting signatures of his own, on the heels of this news, for a petition to have himself appointed as the wharfinger of this new public wharf. A job he was already doing. On August 17th Mr. Lacey met with Sir William Whiteway to suggest his appointment to the position. It’s claimed he was told it was his. So it came as a shock when Magistrate Blandford posted a notice that October which appointed the position of wharfinger to shoemaker Mr. Edward Doheny. This news was quite unexpected and caused much excitement among the populace. William Lacey did not take it well. He knocked on doors across Loading Wharf, Shoal Arm, and The Bight insuring that all who’d signed for him still backed him before appearing before Magistrate Blandford demanding an explanation. He was told that the choice to sue Mr. Burgess had, had consequences (SJEH, 1891, Oct 28).

The new public wharf would be overseen by Mr. Doheny and Mr. Berteau. As a result of this the town would receive a second post office and a savings bank. All this was credited to the political efforts of Mr. Burgess who was much praised.

William Lacey did not get to continue his wharf work. He was last recorded in town storming into the Magistrate’s office that day. I suspect he left not long after. He ended up in La Scie raising his sons as a single father (1921 census). Mr. Lacey fought for the common man and, in the end, he lost that fight. He had his supporters but the support of the working class requires organized resistance and perhaps they just wouldn’t put themselves at risk for his job. He stood up for the men against those in power but made enemies of the powerful. It’s hard to say if he picked the wrong fight in the end. It looks more like he made the structural personal which worked structurally but, the reverse, attempting to make the personal structural didn’t work out for him personally. Maybe it was all the same fight to him. For good or ill he just wasn’t the sort to back down.

I have the petition for the public wharf – here. And I should be getting both of Mr. Lacey’s petitions in the near future (thanks Doyle!). I’ll let you know when I get those transcribed. I’m expecting them to provide insight into Mr. Lacey’s supporters and help me organize Little Bay’s political landscape better. I might even get a glimpse into the union.

In the meantime support your own unions because *gestures wildly above*

Thanks for reading!